Extramedullary tumor

An extramedullary tumor is a tumor localized in the anatomical structures surrounding the spinal cord (roots, vessels, membranes, epidural membrane. Extramedullary tumors are divided into subdural (located under the dura mater) and epidural (located above this membrane). Most extramedullary tumors are meningiomas (arachnoidendotheliomas) and neuromas .

Extramedullary meningioma (arachnoidendothelioma)

Meningiomas are the most common extramedullary tumors of the spinal cord (approximately 50%). Meningiomas are usually located subdurally. They belong to the meningeal-vascular tumors, originate from the meninges or their vessels and are most often tightly fixed to the dura mater.

Extramedullary neuroma

Neuromas occupy the second place among extramedullary tumors of the spinal cord (approximately 40%). Neuromas, developing from Schwann elements of the spinal cord roots, are tumors of dense consistency. Neuromas are usually oval in shape and surrounded by a thin, shiny capsule. In the tissue of neuromas, regressive changes are often found with decay and the formation of cysts of various sizes.

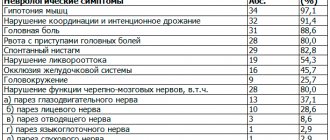

Clinical manifestations of extramedullary tumors

Any lesion that leads to a narrowing of the spinal cord canal and affects the spinal cord is accompanied by the development of neurological symptoms. These disorders are caused by direct compression of the spinal cord and its roots, but are also mediated through hemodynamic disorders.

With extramedullary tumors (both intradural and epidural), symptoms of compression of the spinal cord and its roots appear. The first symptoms are usually local back pain and paresthesia. Then there is a loss of sensitivity below the level of pain, dysfunction of the pelvic organs.

The clinical picture of extramedullary tumors consists of three syndromes:

- radicular;

- half spinal cord syndrome;

- syndrome of complete transverse spinal cord lesion.

The exception is the clinical picture of damage to the cauda equina of the spinal cord (symptoms of multiple damage to the spinal cord roots from the L1 level).

Extramedullary tumors are characterized by early onset of radicular pain, objectively detectable sensitivity disorders only in the area of the affected roots, reduction or disappearance of tendon, periosteal and skin reflexes, the arcs of which pass through the affected roots, local paresis with muscle atrophy according to the lesion of the root.

As the spinal cord is compressed, conduction pain and paresthesia with objective sensitivity disorders occur. When the tumor is located on the lateral, anterolateral and posterolateral surfaces of the spinal cord, in the case of predominant compression of its half, in determining the stage of development of the disease, it is often possible to identify the classic form or elements of Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Over time, symptoms of compression of the entire diameter of the brain appear and this syndrome is replaced by paraparesis or paraplegia. Decreased strength in the limbs and objective sensory disturbances usually first appear in the distal parts of the body and then rise upward to the level of the affected segment of the spinal cord.

The symptom of a cerebrospinal fluid push is a sharp increase in pain along the roots irritated by the tumor. This increase occurs when the jugular veins are compressed due to the spread of increased cerebrospinal fluid pressure to the “displaced” extramedullary subdural tumor. With extramedullary tumors, especially if they are located on the posterior and lateral surfaces of the brain, radicular pain and sometimes conduction paresthesia often occur with percussion or pressure on a certain spinous process.

Intramedullary tumor

An intramedullary tumor is a tumor localized in the substance of the spinal cord. The incidence of intramedullary tumors is 10-18% of the total number of spinal cord tumors. If by their nature intramedullary tumors are often benign and slowly growing, then by their nature of growth and location they are the least favorable from the point of view of the possibility of their surgical removal. Intramedullary tumors of the spinal cord are mainly represented by gliomas ( ependymomas and astrocytomas ). Less commonly found are spongioblastoma multiforme, medulloblastoma, and oligodendroglioma.

Intramedullary ependymoma

Ependymomas most often arise from the ependyma of the central canal at the level of the cervical and lumbar thickenings. They can also develop from the filament terminale and be located between the roots of the cauda equina. Ependymomas are the most common intramedullary tumors. In 50-60% of cases, ependymomas are located at the level of the conus of the spinal cord and the roots of the cauda equina. This is followed by the cervical and thoracic spinal cord. Unlike the cervical and thoracic levels, where the tumor causes thickening of the spinal cord, at the level of the conus and roots it acquires all the properties of an extramedullary tumor. Sometimes ependymomas in this area can completely fill the spinal canal, reaching 4-8 cm in length. Ependymomas are classified as benign, slow-growing tumors. They differ from other spinal cord gliomas in their abundant blood supply, which can lead to the development of subarachnoid and intratumor hemorrhages. In more than 45% of cases, ependymomas contain cysts of varying sizes.

Intramedullary astrocytoma

Astrocytomas are characterized by infiltrative growth, are localized in the gray matter and are widely distributed along the length of the brain. Astrocytoma is the second most common intramedullary tumor after ependymoma in adults and accounts for 24-30% of all intramedullary neoplasms. In this age group, the peak incidence of tumors occurs in the 3rd and 4th decades of life. In children, on the contrary, astrocytoma is observed more often than ependymomas, accounting for up to 4% of all primary tumors of the central nervous system.

Diagnosis of intramedullary tumors

Radiological diagnosis of intramedullary tumors is quite widely developed, but most methods that can adequately judge the presence of a tumor lesion are labor-intensive and traumatic. One of the most sensitive methods in determining changes in the size of the spinal cord is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), therefore, if the presence of an intramedullary tumor is suspected, the growth of which is usually accompanied by thickening of the spinal cord, the use of MRI should be considered the most appropriate.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in St. Petersburg

MRI of the spine. Axial T2-weighted MRI of the thoracic region. Hourglass neuroma. Color processing of the image.

MRI of the spine can detect not only degenerative diseases and disc herniations, but also tumors. Extradural tumors, mainly metastases to the vertebrae, are discussed by us in a special article. Intradural tumors can be extramedullary (inside the spinal canal, but outside the spinal cord) and intramedullary (the spinal cord itself). Both of them can manifest as myelopathic syndrome. MRI in St. Petersburg of the spinal cord is carried out simultaneously with MRI of the spine according to standard programs, with the addition of MRI with contrast. A strong suspicion of a brain tumor allows for targeted examination of the area. On an open MRI, the slices are slightly thicker, however, this usually does not affect the quality of diagnosis. MRI of St. Petersburg allows you to choose the location of the MRI; we recommend that you be examined by us, as we have extensive experience in MRI of the spine in neurosurgery.

Extramedullary intradural tumors

The overall incidence of extramedullary tumors is about 3 cases per 100 thousand population. In adults, the ratio of extra/intramedullary tumors is 70/30%, in children – 50/50%. Benign tumors are most often found in the intradural space. Of these, the majority are meningiomas and neuromas. Much less common are neurofibromas, ependymomas, paragangliomas and granulocytic sarcomas.

Neuromas (schwannomas) and neurofibromas account for approximately half of the tumors in this location and 35% of all spinal tumors. Histologically, neuromas originate from nerve sheath Schwann cells (lemmocytes) adjacent to the dorsal root. They are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50; in men they appear at a slightly younger age than in women. They are almost always single, encapsulated, located in any region, but a little more often in the lumbar or upper cervical region. Multiple neuromas are extremely rare in neurofibromatosis type II. Neurofibromas are composed of Schwann cells and fibroblasts, some surrounding the dorsal root. They are almost always multiple and are associated with neurofibromatosis type I (Recklinghausen disease). From 2 to 12% of neurofibromas degenerate malignantly, turning into neurofibrosarcomas. Despite the difference in histology, the growth pattern of the tumors is the same. About 15% of them spread into the extradural space through one or more intervertebral foramina, acquiring an “hourglass” appearance. This type of growth is especially typical for cervical localization. On radiographs, hourglass growth can be detected by widening of the intervertebral junction and erosion of the arch root. Clinical manifestations of neuromas and neurofibromas consist of radiculopathic and myelopathic syndromes.

On T1-weighted MRI, both neuromas and neurofibromas are iso- or slightly hypointense relative to the spinal cord. However, there are cases of increased signal due to reduction of T1 by mucopolysaccharides associated with water. Proton density on MRI is increased, and on T2-weighted MRIs they are often heterogeneous, there may be very bright areas where there is a high water content, and relatively low signal, especially in the center. Both tumors contrast well on MRI. Neuromas are round in shape, the boundaries are smooth and clear. Neurofibromas are elongated along the spine, which is better visible on coronal MRI. Sizes can be very different.

It is necessary to differentiate neuromas and neurofibromas from meningiomas. The latter in all regions except the cervical are located more often posteriorly, differ in shape and are usually isointense to the spinal cord on T2-weighted MRI.

MRI of the cervical spine. Neurofibromatosis type II. Multiple neuromas (arrows). T1-weighted MRI with contrast.

MRI of the thoracic spine. Neuroma with intra-extradural type of growth. Coronal T1-weighted MRI, transverse T1-weighted MRI with contrast. Increasing the area of interest.

MRI of the lumbar spine. Neurofibromatosis type I. Multiple neurofibromas (arrows). Sagittal and transverse T1-weighted MRI with contrast, coronal T2-weighted MRI.

Meningiomas account for up to 40% of tumors in this location and 25% of all spinal tumors. Usually diagnosed around the age of 40-50 years. Rarely, spinal meningiomas occur in children (3-6% of all cases of meningiomas) as a manifestation of neurofibromatosis type II. With this disease, meningiomas can be multiple, which accounts for about 2% of meningioma cases. Meningiomas originate from the arachnoid membrane. They are encapsulated, broad based, well vascularized, often contain calcifications, and rarely undergo cystic degeneration. They occur 4 times more often in women than in men. They grow very slowly. 85% of meningiomas are located intradurally, about 6% are extra-intradural, and about 7% are extradural. About 75–80% of meningiomas are located in the thoracic spinal canal, 15–17% in the cervical spine, 3% in the lumbar spine and about 2% in the foramen magnum. Malignant spinal meningiomas have been described in anecdotal observations. Clinical manifestations consist of local back pain and myelopathic syndrome due to spinal cord compression.

On T1-weighted MRI, meningiomas are isointense to the spinal cord. On T2-weighted MRI, fibroblastic meningiomas tend to be of low signal, while other histologic variants are usually of moderately high signal. Contrast enhancement on MRI is rapid and uniform, sometimes including the adjacent dura mater (“dural tails”). Meningiomas are usually semicircular in shape on sagittal and coronal MRIs of the spine, with a wide base facing the membrane. Meningiomas are clearly defined on MRI. Hourglass growth is not typical.

MRI of the thoracic spine. Intradural meningioma in the thoracic region. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI with contrast.

MRI of the cervical spine. Intradural meningioma at the C1/2 level. Sagittal and T1-weighted MRI with contrast.

MRI of the lumbar spine. Intradural meningioma in the lumbar region. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI after contrast.

Intradural extramedullary metastases (leptomeningeal carcinomatosis) originate from malignant tumors of the central nervous system and spread along the pia mater with the flow of cerebrospinal fluid. They are most often observed in childhood. Distant leptomeningeal metastases from cancerous nodes, melanomas and lymphomas, carried through the bloodstream or lymphatic tract, are extremely rare. Characteristic localization of leptomeningeal metastases in the lumbar region.

Sometimes on T1-weighted MRI it is possible to see nodes isointense to the roots of the cauda equina. On T2-weighted MRI they often merge with the cerebrospinal fluid. Therefore, if a patient has a tumor known for frequent metastasis, it is imperative to perform an MRI with contrast. At the same time, the absence of metastases according to MRI results should be additionally confirmed by multiple cytological analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid.

MRI of the cervical spine. Leptomeningeal metastases (arrows). Sagittal T1-weighted MRI with contrast.

Extramedullary ependymomas grow from the cone and filum terminale. According to histology, they belong to the myxopapillary type. They make up about 13% of all spinal ependymomas. They are diagnosed at the age of about 40 years and slightly more often in men. Although they belong to grade 1, dissemination with cerebrospinal fluid flow occurs.

On T1-weighted MRI of the lumbar spine, ependymomas are isointense to the spinal cord. They are hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI. They usually contrast well and evenly, although peripheral enhancement also occurs. Rarely, subarachnoid dissemination occurs. There may be a high protein content in the cerebrospinal fluid, which is manifested by an increased signal from it on T1-weighted MRI. In this case, the roots are not visible. Subarachnoid hemorrhages with characteristic hemosiderin depots on the surface of the involved structures have been described in ependymoma.

MRI of the lumbar spine. Myxopapillary ependymoma. T1-weighted MRI after contrast. Increase.

Ganglioneuroma (paraganglioma) originates from cells of the autonomic nervous system. The frequency is 1 case per 100 thousand population. The tumor can be localized anywhere. Spinal ganglineuroma usually has an extradural type of growth, but intradural growth also occurs occasionally. Appears at the age of 40–50 years. Slightly more common in men.

On T1-weighted MRI, the tumor is isointense to the spinal cord. It is hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI and a fibrous capsule may be visible. Contrast enhancement on MRI is good but uneven. Since intradural paraganglioma is localized in the region of the cauda equina and filum terminale, it is impossible to distinguish it from ependymoma by MRI signs.

MRI of the lumbar spine. Paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI after contrast.

Intramedullary tumors

Intramedullary tumors account for 10-20% of all intradural formations. In adults, astrocytoma, myxopapillary ependymoma, hemangioblastoma and metastases have intramedullary localization; in children - pilocytic astrocytoma, ependymoma, ganglioglioma.

Astrocytoma accounts for 30-50% of intramedullary tumors. Most often, spinal astrocytoma belongs to the benign pilocytic subtype (G I-II); poorly differentiated astrocytoma and glioblastoma are rare. Usually observed in childhood or middle age without gender predisposition. The typical location is the upper thoracic level, but astrocytoma of the cervical and cervicocranial localization may occur. The tumor grows along the length of the spinal cord, but an exophytic type of growth also occurs. In the transverse plane it tends to be posterior.

MRI reveals spinal cord swelling, the mass is iso- or hypointense on T1-weighted MRI, and the tumor nodule, edema, and cyst may be equally hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI. Sometimes the cyst differs in signal from the node due to the admixture of protein or blood. The node is well contrasted, often does not have clear boundaries and is heterogeneous (“spotty”) in structure. Reactive cysts are observed in 30% of cases; they are located above and (or) below the node and are not contrasted. Necrotic intratumoral cysts are contrasted along the periphery, and when visualized after 20-30 minutes, they can be contrasted entirely.

MRI of the cervical spine. Intramedullary astrocytoma. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI with contrast.

Ependymoma is the second most common intramedullary tumor after astrocytoma. One third of ependymomas have spinal localization, 2/3 are located in the ventricles of the brain. The tumor occurs at any age, but the peak occurs in middle age. It develops more often in men. Typical localization in adults is the area of the cauda equina and filum terminale; these ependymomas belong to the myxopapillary subtype. In children, ependymomas have cervical and cervicocranial localization. Ependymomas grow slowly along the length of the spinal cord, causing erosion of the pedicles and posterior segments of the vertebral bodies over time. In the axial plane they are located centrally, symmetrically occupying the diameter of the spinal cord. Reactive cysts are observed in 50% of cases, more often than with astrocytomas.

Like astrocytoma, ependymoma is hypointense on T1-weighted MRI and hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI. However, hemorrhages are more common, usually at the poles of the node. After contrasting, the node is visible as clearly defined (due to the capsule) and homogeneous.

MRI of the cervical spine. Ependymoma of the cervical spinal cord. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI after contrast.

Hemangioblastoma is observed much less frequently (about 2-6%) than astrocytoma and ependymoma. Occurs more often in middle age. In approximately a third of cases, it is a manifestation of Hippel-Lindau disease, then it is observed in a younger cohort of patients and can be multiple. Spinal hemangioblastoma is accompanied by a reactive cyst, with features resembling a syringomyelitic one.

MRI of the spine reveals an iso- or hypointense spinal cord nodule on T1-weighted MRI and a large CSF cyst or slightly increased signal intensity. T2-weighted MRIs sometimes show dilated vessels, especially along the posterior surface of the spinal cord. After MRI with contrast, the node becomes bright and clearly defined.

MRI of the cervical spine. Intramedullary hemangioblastoma. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI after contrast.

Metastases to the spinal cord are very rare. From the primary node they enter through the hematogenous route. Metastases can be single or multiple, sometimes combined with metastases to the vertebrae.

MRI in St. Petersburg USA