Medulloblastomas are cerebellar tumors that account for 30-40% of all posterior fossa tumors in children. Medulloblastoma is considered one of the most malignant brain tumors in children. New methods of treating and diagnosing patients have significantly improved the prognosis, however, an optimal treatment algorithm for this disease has not yet been developed.

Up to 65-85% of medulloblastomas occur before the age of 15 years. The peak incidence occurs at the age of 5-7 years. Boys get sick more often than girls and their ratio ranges from 1.7:1 to 2.5:1.

Etiology

Medulloblastomas belong to the group of embryonal neuroepithelial tumors. It is believed that medulloblastomas develop from cells of the outer granular layer of the cerebellum and the posterior cerebellar velum. There are 2 types of medulloblastomas: “classical” type medulloblastomas and dysmoplastic medulloblastomas.

Medulloblastomas disseminate through the cerebrospinal fluid system, producing metastatic nodes in the subarachnoid space of the brain and spinal cord, in the walls of the ventricles, in the area of the chiasm, and in the basal parts of the brain. It is extremely rare that metastases occur extracranially - in the bone marrow, lungs, and liver.

Clinical picture

Medulloblastomas are characterized by the same symptoms as other tumors of this location.

All signs of a growing cerebellar tumor can be divided into three groups:

cerebral (develop due to increased intracranial pressure);

distant (occur at a distance, that is, not directly next to the tumor)

focal (actually cerebellar).

In almost all cases, these three groups of symptoms occur simultaneously with each other, just the severity of certain symptoms varies. This is largely determined by the direction of tumor growth and compression of individual adjacent structures.

The special location of the cerebellum in the cranial cavity determines some features of the clinical course of its tumors. A clinical situation is possible when the first signs of a tumor are general cerebral and even distant symptoms. This is due to the fact that the cerebellum is located above the fourth ventricle and brain stem. Therefore, sometimes the first symptoms of a cerebellar neoplasm are signs of damage to the brain stem and disruption of the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the fourth ventricle, and not the cerebellum itself. And the damage to the cerebellar tissue is compensated for some time, which means it does not manifest itself in anything.

Focal symptoms:

The cerebellum consists of several parts: the central one - the vermis and the hemispheres located on the sides of it (left and right). Depending on which part of the cerebellum the tumor is compressing, different symptoms occur.

If the worm is affected, the following symptoms appear: difficulty standing and walking. A person sways when walking and even while standing, stumbles out of the blue and falls. The gait resembles the movement of a drunk; when turning, it “skids” to the side. To stay in place, he needs to spread his legs wide apart and balance with his hands. As the tumor grows, instability occurs even in a sitting position.

If a tumor grows in the area of one of the cerebellar hemispheres, then the smoothness, accuracy and proportionality of movements on the side of the tumor (that is, left or right) are disrupted. A person misses when trying to grab an object; he is unable to perform actions associated with rapid contraction of antagonist muscles (flexors and extensors). On the affected side, muscle tone decreases. The handwriting changes: the letters become large and uneven, as if zigzag. Speech disturbances are possible: it becomes chanting, divided into syllables. Trembling appears in the limbs on the side of the tumor, which intensifies towards the end of the movement performed.

As the tumor grows, the symptoms of damage to the worm and hemispheres gradually mix, the process becomes bilateral.

In addition to the above symptoms, the patient may exhibit nystagmus.

The proximity of the cerebellar tumor to the fourth ventricle causes disruption of the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid. Internal hydrocephalus develops with headaches, attacks of vomiting and nausea. Overlapping of the openings of the fourth ventricle may be accompanied by Bruns syndrome. This can occur when there is a sudden change in the position of the head (especially when bending forward), due to which the tumor moves and blocks the openings for the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid. The syndrome is manifested by a sharp headache, uncontrollable vomiting, severe dizziness, temporary loss of vision, and confusion. At the same time, disturbances in the activity of the heart and respiratory organs appear, posing a danger to life.

A distinctive feature of medulloblastomas from other tumors of this localization is only a short history of the disease - most often from 3 months to six months, less often - longer (with modern diagnostic methods). As a rule, the disease manifests itself with headache, nausea, the appearance of cerebellar and brainstem symptoms, congestive optic discs, which is caused by the development of occlusive hydrocephalus and the direct local effect of the tumor. Hydrocephalus of varying severity is diagnosed in most cases (up to 85%).

To the features of the course of cerebellar tumors

Relevance of the problem. In the structure of tumors of the posterior cranial fossa, cerebellar neoplasms occupy about 70.6-73.6% [1]. Cerebellar tumors can be either benign (astrocytomas), characterized by slow growth, or malignant, infiltratively growing (medulloblastomas). Medulloblastomas account for about 20.0% of all primary tumors of the central nervous system in children. In the United States, 2 new cases of medulloblastoma are detected annually per 1 million white population, 1 case per 1 million black population, and 1,700 affected children are diagnosed annually under the age of 18 [4]. In adults they are extremely rare - annually 5-6 new cases per 10 million [5,6]. Every year, 1.4 per 100,000 children under 16 years of age suffer from cerebellar tumors in Russia, which is approximately 450 new cases per year [2].

In the morbidity structure, 2 peaks are identified - from 3 to 4 and from 8 to 9 years [7]. Intracranial hypertension syndrome and hydrocephalus are clinically manifested by headache, often forced head position, nausea, and vomiting. Disturbances of consciousness and convulsive seizures are possible [8].

The slow growth of the tumor and its location in close proximity to liquor-containing spaces create good conditions for the development of compensatory mechanisms of the brain, due to which clinical manifestations occur at later stages of the disease, when the tumor reaches a large size and poses certain difficulties for surgical treatment [3].

Damage to the cerebellum, primarily to its vermis, causes a violation of the statics of the body - the ability to maintain a stable position of its center of gravity, ensuring stability. When this function is disrupted, static ataxia occurs. The patient becomes unstable, so in a standing position he tends to spread his legs wide and balances with his hands. With isolated damage to the hemispheres, coordination disorders are observed, accompanied by instability, body swaying and falling [4].

Until now, and often, patients with such pathologies receive unqualified treatment for a long time from pediatricians, infectious disease specialists, neurologists, and are hospitalized in neurosurgical departments in advanced, decompensated states.

It is appropriate to note that despite the presence of numerous works covering the course and methods of treating cerebellar tumors, clinical symptoms, especially early signs, are not sufficiently presented in them and therefore we consider it appropriate to conduct new research in this direction.

Purpose of the study. The purpose of our study was to study the features of the clinical course of cerebellar tumors.

Materials and methods of research. This study included data from clinical and neurological examinations of 35 patients (21 women, 14 men). The average age of the patients was 30 years (with a corresponding variation from 3 to 69 years), who were inpatient treatment in the department of neurosurgery of the clinic of the Samarkand Medical Institute (SamMI) for cerebellar tumors from 2012 to 2014. It included 10 (28.5%) patients with tumors localized in the cerebellar vermis, 8 (22.8%) patients in the cerebellopontine angle, 8 (22.8%) patients in the left hemisphere, 5 (14.2 %) of patients in the right hemisphere, 4 (11.4%) patients in the IV ventricle. All patients underwent a comprehensive examination, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Research results and discussion. The clinical picture of cerebellar tumors was characterized by gradual progression of cerebellar and cerebellar-vestibular symptoms associated with local damage to the cerebellar tissue, stem syndrome, depending on compression of the trunk at the level of the posterior cranial fossa, as well as dysfunction of the cranial nerves and the syndrome of increased intracranial pressure caused by ventricular hydrocephalus.

An early symptom of the disease was headache, which was often accompanied by vomiting. Early symptoms of cerebellar tumors also include incoordination , nystagmus, and muscle hypotonia.

Gradual progression of intracranial pressure was accompanied by vomiting in 28 patients (80.0%), it was often observed simultaneously with dizziness in 9 patients (25.7%), forced position of the head and torso (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of occurrence of neurological symptoms in cerebellar tumors

The most common symptom of cerebellar tumors was muscle hypotonia in the extremities, which was observed in 34 patients (97.1%). Violation of posture and position was detected in 32 patients (91.4%), which manifested itself with a fixed position of the head and throwing it back or bending forward.

Cerebellar tumors were characterized by dysfunction of the cranial nerves (80.0%), among oculomotor disorders, the most distinct were quadrigeminal paresis and upward gaze paralysis, observed in 13 patients (37.2%), indicating progression of trunk compression. Spontaneous nystagmus was observed in 29 patients (82.8%), paresis of the abducens nerve in 3 patients (8.6%), facial in 10 patients (28.6%), auditory and glossopharyngeal in 1 patient each (2.9%), related to late symptoms, while paresis of the soft palate was detected mainly on one side.

The life-threatening conditions for patients with cerebellar tumors were the syndrome of prolapse of the cerebellar tonsil and its entrapment in the foramen magnum. Symptoms of an occlusive attack were caused by a rapidly increasing delay in the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the ventricular system as a result of complete (or almost complete) or temporary obliteration (blockage) of the outflow tract, observed in 19 patients (54.3%). Long-term hypertension contributed to the occurrence of occlusive hydrocephalus, which was observed in 16 patients (45.7%). Occlusive hydrocephalus was also accompanied by intraventricular hypertension and compression of the brain stem.

Conclusions:

1. An early symptom of cerebellar tumors is headache, which is accompanied by vomiting, loss of coordination, nystagmus and muscle hypotonia.

2. The progression of cerebral symptoms depends on either complete partial blockade of the cerebrospinal fluid circulation pathways or occlusion of the ventricular system. The leading general cerebral symptoms include headache (88.6%), vomiting (80.0%), dizziness (25.7%).

3. Cerebellar tumors are characterized by progression of focal symptoms. Among the focal symptoms, muscle hypotonia (97.1%), loss of coordination (91.4%), spontaneous nystagmus (82.8%) and dysfunction of the cranial nerves - paresis of the oculomotor (37.2%), facial (28 .6%), abducens (8.6%) nerves.

4. Determining the patterns of occurrence and progression of the listed symptoms of cerebellar tumors contributes to the timely detection and prevention of life-threatening complications of cerebellar tumors.

Diagnostics

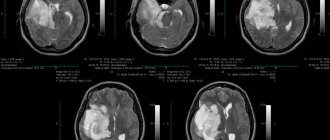

The main diagnostic methods today are CT and MRI. Typically, the tumor is located in the midline (85%), less often in the hemispheres of the cerebellum (15%). Most often, these are delimited formations that accumulate contrast material well, growing into the lumen or completely filling the fourth ventricle. Heterogeneity of contrast enhancement is usually due to areas of necrosis in the tumor. The most sensitive imaging modality is contrast-enhanced MRI. On sagiattal sections, it is possible to more accurately establish the relationship of the tumor to the superior vermis, tegmentum of the midbrain, vein of Galen, and cervicomedullary junction. However, even MRI does not always answer the question of whether the tumor grows into the bottom of the rhomboid fossa.

On CT, medulloblastomas are usually hyper- or isodense; on MRI, T1-weighted images have a reduced signal, which allows them to be distinguished from other tumors.

Posterior fossa tumors

Ependymoma

Ependymomas account for approximately 6–12% of all intracranial tumors and occur primarily in children and adolescents (average age approximately 6 years). There is a second age peak – at 30–40 years.

Ependymomas arise from the ependymal lining of the ventricles and the central canal of the spinal cord. They are slow-growing, solid, well-circumscribed tumors that displace rather than infiltrate the surrounding brain parenchyma and are classified as WHO grade II tumors.

Radiological findings

Common signs include hemorrhage and calcification. Cystic changes are more common in supratentorial ependymomas.

CT

Ependymomas are usually isodense compared with the brain on non-contrast CT. Large areas of calcification (50%), cysts (15%), and hemorrhage (10%) are common findings and contribute to the heterogeneous appearance of the tumor.

MRI

On MRI, ependymomas appear as well-circumscribed neoplasms, somewhat hypointense relative to gray matter on short TR images and hyperintense with long TR. Cystic areas (more hyperintense) and calcifications (hypointense) create a heterogeneous appearance on long TR images. There is moderate accumulation of contrast in the solid node. Spread through the foramina from the fourth ventricle into the cerebellopontine angle or into the cisterna magna is a characteristic feature of these tumors and may help in differentiation from other tumors of the pediatric PCF.

Brain stem glioma

Brainstem gliomas represent an extremely heterogeneous group of brain tumors and account for approximately 15% of all childhood CNS neoplasms.

Clinical symptoms depend on the involvement of the cranial nerve nuclei and brainstem pathways in the tumor.

Radiological findings

Brainstem gliomas arise in the pons (most commonly), midbrain, or medulla oblongata and can be diffuse, focal, or mixed. The majority of brainstem gliomas (60%) are considered low-grade tumors, although histologic heterogeneity is common, even within the same tumor.

CT

On CT scan, in typical cases, truncal glioma appears as focal, hypo- and isodense-density, with pontine expansion, with extremely variable enhancement that may change over time. The degree of enhancement does not significantly correlate with tumor malignancy or survival rate. However, the presence of hypoattenuating areas and involvement of the entire brainstem are correlated with poor outcome.

MRI

MRI shows typical T1 and T2 prolongation. Long TR images provide a better assessment of the true extent of the tumor due to the hyperintense contrast with normal white matter. Hydrocephalus is a rare symptom of truncal gliomas due to their slow growth. Hemorrhages or cysts occur in 25% of cases, more often with focal rather than diffuse growth. Approximately one third of the images of these tumors are enhanced by contrast material. The accumulation of the latter is not a reliable prognostic sign.

Hemangioblastoma (angioreticuloma)

Hemangioblastoma (angioreticuloma) is a benign, usually solitary tumor of complex histogenesis. The most common site of tumor occurrence is the cerebellar hemisphere, followed by the cervical spinal cord, medulla oblongata, and cerebral hemispheres (rarely). Nodular, cystic and mixed forms may occur.

Clinical symptoms are associated with occlusive hydrocephalus.

Radiological findings

MRI

The most common imaging appearance (60% of all cases) is a well-circumscribed cystic tumor with an intensely enhancing mural nodule. Due to the fact that the vascular supply of the tumor comes entirely from the soft membranes, the node representing the tumor itself is almost always located superficially. On MRI, hemangioblastoma appears as a cystic tumor, hypointense relative to gray matter on short TR images and hyperintense with long TR. Surrounding swelling may or may not be present. Sometimes spontaneous hemorrhage is detected. Due to the high vascularity of this neoplasm, images may reveal convoluted areas of lack of flow signal in the tumor node, and intense accumulation of contrast is also noted. Up to 40% of hemangioblastomas are entirely solid tumors with poorly defined margins and enhancement of the solid part.

Angiography

In clinically suspicious cases, if CT and MRI are negative, angiography may be helpful, revealing a small (sometimes less than 1 cm), well-vascularized nodule.

Source

- V. N. Kornienko BRAIN TUMORS Research Institute of Neurosurgery named after. N. N. Burdenko RAMS, Moscow

- Radiopaedia

1. Brain imaging. Laurie A. Loevner. St. Louis: Mosby, c1999. ISBN:032300430X (find it at amazon.com)

- 2. Pediatric neuroimaging. A. James Barkovich. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, c2005. ISBN:0781757665 (find it at amazon.com)

- 3. Diagnostic Neuroradiology. Valery N. Kornienko, Igor Nikolaevich Pronin. Springer ISBN:3540756523 (find it at amazon.com)

Tumor stages and metastasis

Among the many factors that influence the prognosis of the disease, the extent of the tumor is extremely important. Two main parameters are taken into account here: the size and infiltration of the primary tumor (T-stage) and the degree of its dissemination or metastasis (M-stage).

T stage

T1 - tumor less than 3 cm in diameter: in the roof of the IV ventricle, vermis, or cerebellar hemisphere.

T2 - a tumor more than 3 cm in diameter, affects one nearby structure or partially fills the fourth ventricle.

T3a - affects two adjacent structures or fills the fourth ventricle with spread into the cerebral aqueduct or the foramina of Magendie and/or Luschka.

T3b - the tumor grows into the bottom of the fourth ventricle and fills the cavity of the fourth ventricle.

T4 - the tumor spreads further through the cerebral aqueduct and affects the midbrain and third ventricle.

M stage

M0 - there are no signs of subarachnoid or hematogenous metastases.

M1 - tumor cells in the cerebrospinal fluid.

M2 - a node in the cerebellum or subarachnoid space, or in the third or lateral ventricles.

M3 - nodes in the spinal arachnoid space.

M4 - extracranial metastases.

The T stage is determined during surgery, when the surgeon can directly determine the boundaries and extent of the tumor. In most cases, T3-T4 stages of the disease predominate. Their share ranges from 50% to 65%. Medulloblastoma tends to metastasize along the cerebrospinal fluid pathways and, less often, extracranially. In general, at the time of diagnosis, 20%-30% of patients already have metastases. In young children this figure reaches 50%. Moreover, about 15% of metastases are supratentorial, about 12% are spinal. In approximately 10% of cases, extracranial metastases are detected - most often in the bones (up to 80%), less often - in the lungs, liver, and peritoneum.

Stages M2-M3 are determined on the basis of MRI and CT with contrast enhancement of the brain and spinal cord, spinal metastases are detected using myelography.

Extracranial metastases are detected by ultrasound of internal organs, scintigraphy, and examination of a puncture biopsy of the bone marrow.

Symptoms

The picture of the disease in cerebellar tumors consists of general cerebral, cerebellar symptoms, and phenomena of damage to the brain stem. Very often, all three groups of symptoms appear simultaneously.

Sometimes the onset of the disease is manifested by symptoms of one type. General cerebral phenomena occur first if the tumor is localized in the cerebellar vermis. The process taking place at this time directly in the tissues of the cerebellum may not produce any symptoms and remain in the compensation stage for a long time. Symptoms of cranial nerve damage or indications of brainstem compression may also be the first manifestations of the disease.

Tumor diseases of the cerebellum have the same general cerebral symptoms as tumors of the cerebral hemispheres. Patients report constant headaches, sometimes of a paroxysmal, progressive nature. The headache comes in the morning, is widespread, and is less often centralized in the back of the head. The feeling of nausea comes regardless of food. At the peak of the headache, vomiting, dizziness, stunned state, and drowsiness are possible.

Patients complain of fatigue. Sometimes hallucinations of the olfactory, auditory or light type develop. The more the tumor blocks the vessels through which the cerebrospinal fluid passes, the more the clinical picture increases. The patient is forced to take a position that alleviates his condition - tilt his head forward or backward, knee-elbow position with his head down.

Attacks of nausea and vomiting come more often. If the patient suddenly changes the position of the head, sudden blocking and the onset of a hypertensive-hydrocephalic crisis are possible.

Focal (cerebellar) signs depend on the location of the tumor process. Cerebellar ataxia is the main clinical factor. If the process is located in the cerebellar vermis, instability and gait disturbances are observed. When walking, the patient stumbles, staggers, and spreads his legs wide. To maintain balance, the patient balances with his hands. The patient may skid when turning.

Involuntary movements of the eyeballs are observed - nystagmus. Cerebellar speech disorders develop. It has an intermittent and chanting character (divided into syllables). When the cerebellar hemispheres are involved in the tumor process, disorders of coordination and proportionality of movements are noted on the affected side. The patient cannot perform finger-nose, knee-heel tests. There are changes in handwriting to a more sweeping, larger one, as well as dysmetria and intention tremor.

A cerebellar neoplasm can grow from one hemisphere of the cerebellum to the other, from the hemisphere to the vermis and vice versa. Impaired coordination and confusion of symptoms of damage to the cerebellar structures are manifested in a variety of clinical pictures.

Damage to the brain stem has its own signs of compression, as well as dysfunction of individual cranial nerves. Patients experience trigeminal neuralgia, neuritis of the facial nerve, hearing impairment, pathologies of taste perception, speech impairment, and complete loss of sensitivity of the soft palate.

Vomiting not associated with headache is a typical manifestation of brainstem lesions. It is caused by irritation of the receptors in the posterior fossa of the skull and can appear due to sudden movements or changes in body position. Long-term compression of the brainstem provokes motor restlessness, irregular heartbeat, double vision, increasing nystagmus, oculomotor disorders - gaze paresis, divergent strabismus, drooping eyelid, mydriasis.

Possible autonomic disorders, tonic convulsions, arrhythmia. Impairment of respiratory activity is possible until breathing stops completely, which can lead to the death of the patient.

Treatment strategy

Treatment of patients with medulloblastomas currently consists of three stages: surgical removal of the tumor and restoration of normal cerebrospinal fluid circulation, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Complex therapy begins with tumor removal. With timely comprehensive treatment, the 50-year survival rate of patients with medulloblastomas is 70-80%. The progress of surgical technology (use of a microscope, ultrasonic suction), anesthesiology and resuscitation has significantly affected the reduction of surgical mortality, as well as increasing the radicality of tumor removal.

Treatment of cerebellar tumor

Treatment is prescribed only after confirmation of the diagnosis by a medical specialist. Surgical treatment, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, symptomatic treatment (hormones, analgesics, antiemetics, sedatives, diuretics) are used.

Essential drugs

There are contraindications. Specialist consultation is required.

- Diclofenac (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 200 mg/day. for 2 doses. Per course 2000 mg.

- Diazepam (tranquilizer). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 5 mg/day.

- Haloperidol (antipsychotic). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 5 mg/day. for 2-3 doses.

- Amitriptyline (antidepressant). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 25 mg/day.

- Carbamazepine (anticonvulsant). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 900 mg/day. for 3 doses. Per course 12600 mg.

- Prednisolone (glucocorticosteroid drug). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 30 mg/day. for 2-3 doses.

- Domperidone (antiemetic). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 60 mg/day. for 3 doses. Per course 420 mg.

- Hydrochlorothiazide (diuretic). Dosage regimen: orally, at a dose of 100 mg/day. in 2-4 doses.