Febrile seizures have been known since antiquity. Hippocrates wrote that febrile seizures most often occur in children in the first 7 years of life and much less frequently in older children and adults (1). Febrile seizures represent an important problem in pediatrics. The relevance of the problem of febrile seizures is determined, first of all, by their potential to transform into various benign and resistant epileptic syndromes, and also, in the case of a status course, often influence neuropsychic development.

Clinical practice shows that the diagnosis of “febrile seizures” is sometimes interpreted too generally, and doctors classify all seizures accompanied by high fever as febrile seizures. This leads to “missing” dangerous neuroinfections and inadequate prediction of febrile seizures.

Differential diagnosis between epilepsy and simple febrile seizures sometimes causes difficulties and depends more on the duration and observation of patients than on laboratory data (2) True AF should be distinguished from febrile-provoked seizures, which can be part of a number of forms of epilepsy (most often - the syndrome Drave).

Numerous studies worldwide have shown that the incidence of AF in the pediatric population averages 2–5% (3). An increased incidence of AF was noted in certain geographic regions. Thus, in Japan, AF occurs in 8.8% of children (4), in India - in 5.1–10.1%, and on the islands of Oceania - in 14% of the child population (3).

The typical age interval for the onset of AF is from 6 months. up to 5 years with a peak at 18–22 months of life. Febrile seizures are more common in boys (60% of cases) (5).

Clinical manifestations

The following factors are of utmost importance in the determination of AF: genetic predisposition, perinatal pathology of the central nervous system and hyperthermia. Most scientists agree that genetic factors play a leading role in the development of AF (6).

Many researchers (domestic and foreign) identify risk factors related to the subsequent development of epilepsy in children with febrile seizures:

- the presence of epilepsy or epileptic seizures in childhood in parents;

- neurological pathology in a child before the onset of febrile seizures;

- impaired mental function;

- focal seizures (predominance of seizures on any side of the body, head turns, facial distortion, etc.);

- prolonged convulsions (lasting more than 15 minutes);

- convulsions repeated within 24-48 hours;

- the presence of repeated febrile convulsions or other paroxysmal conditions (frequent shuddering in sleep, night terrors, sleepwalking, fainting, etc.);

- pathological changes in the electroencephalogram (EEG) that persist for more than 7 days after the attack;

- the child's age is less than 1 year or more than 5 years;

- the appearance of attacks when the temperature drops.

If there are 2 or more risk factors, long-term treatment with antiepileptic drugs is usually prescribed.

Dynamic observations of children who suffered single febrile seizures showed that the risk of a repeated febrile seizure is 30%, and epileptic seizures not associated with an increase in temperature are 2-5%. If the child was less than a year old, the risk of recurrent seizures increases to 50% (2).

The likelihood of epilepsy in the presence of 2 or more risk factors is much higher and can reach 25%.

The negative impact of febrile seizures on the neurological status and mental development of the child has not been proven. Of particular interest is the effect of febrile seizures on the subsequent development of epilepsy. There is evidence that febrile seizures can sometimes lead to “epileptization” of the brain. At the same time, importance is attached to the factor of oxygen starvation of brain cells - hypoxia, which occurs during seizures and leads to structural changes in the cells of the temporal regions of the brain with the subsequent formation of an epileptic focus (4).

In this regard, it seems extremely important to us, and many other scientists and fellow neurologists, to conduct at least a routine EEG after the first or repeated attack.

There is no generally accepted classification of febrile seizures. It is proposed to distinguish between typical (simple) and atypical (complex) AF (7) (Table 1). Typical (simple) AF accounts for 75% of all febrile seizures. In the vast majority of cases, simple AF goes away on its own with age, transforming into epilepsy in only 3–5% of cases, mainly in idiopathic focal forms (8; 5).

We propose the following, more complete, syndromic classification of febrile seizures.

- Typical (simple) febrile seizures.

- Atypical (complex) febrile seizures.

- Idiopathic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus.

- Febrile seizures at the onset of various epileptic syndromes.

- Hemiconvulsive seizures, hemiplegia, epilepsy syndrome (HHE syndrome).

- Destructive epileptic encephalopathy in school-age children (DESC syndrome).

Simple (typical) AF makes up the vast majority of all febrile attacks - up to 75% (7). They are characterized by the following characteristics: Age of debut from 6 months. up to 5 years. High percentage of familial cases of AF and idiopathic epilepsy among relatives of the proband. Seizures are usually generalized convulsive tonic-clonic; often associated with sleep.

The duration of attacks is less than 15 minutes, in most cases 1–3 minutes; the attacks stop on their own.

High probability of recurrence of AF. Occurs in neurologically healthy children. Epileptiform activity is not recorded on the EEG in the interictal period. There are no changes in the brain during neuroimaging. AF goes away on its own after reaching the age of 5 years.

Complex (atypical) AF is long-lasting, often focal and frequent AF. Atypical AF transforms into symptomatic focal epilepsy (usually paleocortical temporal epilepsy) in 15% of patients (10). In these cases, MRI examination often reveals sclerosis of the horn of Ammon. In patients with a history of resistant focal forms of epilepsy, atypical AF is often detected - up to 30% of cases (8). Below are the characteristic features of atypical AF.

- The age of debut ranges from several months to 6 years.

- Absence of familial cases of AF and epilepsy among relatives of the proband.

- Seizures are generalized tonic-clonic or secondary generalized (often with a predominance of a focal clonic component), less often focal motor (including hemiclonic) or automotor.

- The duration of attacks is more than 30 minutes; development of status epilepticus is possible. The occurrence of post-attack symptoms of prolapse (Todd's paresis, speech disorders, etc.) is common.

- High frequency of AF, often during the period of one febrile illness.

- The presence of focal neurological symptoms in the neurological status (for example, hemiparesis); delays in mental, motor or speech development.

- The presence of continued regional slowing in an EEG study, most often in one of the temporal leads.

- Detection of structural changes in the brain by neuroimaging (typically hippocampal sclerosis), which may not occur immediately after AF, but develop with age.

| Symptoms\Types of AF | Typical AF | Atypical AF |

| Age of debut | from 6 months up to 5 years | up to 1 year or after 5 years |

| Family history | Compounded with epilepsy and AF | Not burdened |

| Types of seizures | SHG | Focal motor, VGSP |

| Duration of attacks | The attacks are short. Most often < 15 min (usually 1-3 min) | The attacks are prolonged. More often > 15 min. Possible status epilepticus |

| Repeated attacks in one period of fever | Not typical | Characteristic |

| Seizure frequency | Low | High |

| Post-attack symptoms of prolapse | Not typical | Possible |

| Focal neurological symptoms | Not typical | Possible |

| Brain changes on neuroimaging | Not typical | Possible |

| Basic activity on EEG | Within the age norm | More often slowed down |

| Regional slowing on EEG | Not typical | Maybe |

| Epileptiform activity | Not typical. Possible in 2-3% of cases: DEPD or short diffuse peak-wave discharges | Possible. More often regional epileptiform activity |

| Risk of transformation to epilepsy | Short | High enough |

Treatment of an acute episode of febrile seizures

The first episode of febrile seizures inevitably raises a number of fundamental questions for both parents and clinicians. The most important of them are:

- Why did febrile seizures occur?

- What is their prognosis, i.e., the likelihood of recurrence, transformation into epilepsy?

- What is the impact on the child’s health, in particular on neuropsychological development?

- What are the tactics of therapy and prevention?

As a rule, young parents who encounter an acute episode of febrile seizures for the first time are psychologically unprepared, confused, and do not know what their actions should be.

When a diagnosis of “febrile convulsions” is made, the doctor’s initial task is to provide emergency assistance to the patient and conduct an explanatory conversation with parents on the possible nature of febrile convulsions and measures to prevent them.

Emergency care includes, first of all, ensuring the optimal position of the patient - on his side, with his head lowered slightly below the body. You should also provide the child with a certain comfort, access to fresh air, and free him from excess clothing. However, although the attack is provoked by high temperature, excessive hypothermia should also be avoided. Clinical experience shows that cold baths, rubbing with alcohol, and the use of fans do not provide a significant beneficial effect and sometimes cause discomfort, which negatively affects the course of paroxysms. This is due to the fact that a strong decrease in temperature can cause metabolic disturbances in the body, which contribute to a second wave of temperature reaction in response to infection.

Of the anticonvulsants, the most useful for the correction of febrile seizures is intravenous administration of diazepam (Valium) - 0.2-0.5 mg/kg, lorazepam (Ativan) - 0.005-0.20 mg/kg, phenobarbital - 10-20 mg/kg. In the case of status febrile seizures, intubation should be performed and oxygen should be given in doses. It is also necessary to administer a 5% dextrose solution.

Along with intensive therapy, already at the first episode of febrile seizures, it is very important to conduct an explanatory conversation with parents. The attention of parents should first of all be drawn to the benign course of febrile seizures in most cases (2-5% of outcomes in epilepsy, among which a considerable percentage of transformations into benign epileptic syndromes). That is, parents need to make it clear that the likelihood of transformation of febrile seizures into severe forms of epilepsy is generally low. At the same time, parents should know that the likelihood of developing a repeated paroxysm of febrile seizures is quite high, and it is quite realistic to predict it. It is almost impossible to completely exclude recurrence of febrile seizures. Therefore, it is necessary to teach parents first aid techniques (position of the patient with the head turned to one side, combating overheating, access to fresh air, drinking plenty of fluids, prescribing anticonvulsants recommended by the doctor), a strict definition of the situation - prolonged, more than 30 minutes, febrile convulsions, repeated, within short intervals, paroxysms, when specialized medical care is necessary.

Modern look at febrile seizures

NG Lukshina

Summary

Febrile seizures are the most common type of seizure seen in the pediatric age group.

Experience shows, however, that they do not have a direct effect on cognitive function, so the prognosis for normal neurological function in children with febrile seizures is good. Children with febrile seizures have a slightly higher risk of later developing epilepsy compared with the general population risk (2% versus 1%). Risk factors for further development of epilepsy include complex febrile seizures, a family history of epilepsy or neurological disorders, and the presence of developmental delay. Febrile seizures are divided into 2 types: simple febrile seizures (which are generalized, lasting <15 minutes and do not recur within 24 hours) and complex febrile seizures (which are prolonged, repeat several times in 24 hours, or are focal). Clinicians, when assessing infants or young children following simple febrile seizures, should focus their attention on identifying the cause of the child's fever. Meningitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any febrile child, and therefore a diagnostic lumbar puncture should be performed if there are clinical signs or symptoms suggestive of meningitis. Any child 6 to 12 months of age who is admitted to the hospital with seizures and fever should have a lumbar puncture, especially if the child has not received the Haemophilus influenzae (Hib) or pneumococcal vaccine (i.e., has not received scheduled vaccinations such as recommended), or when immunization status is unknown, due to an increased risk of bacterial meningitis. A spinal tap is an option for children who have been treated with antibiotics. In general, simple febrile seizures usually do not require extensive testing, such as electroencephalography, blood tests, or neuroimaging. Prophylactic treatment for simple febrile seizures is not necessary. Key words:

febrile seizures, neuroimaging, electroencephalography

Summary

Febrile seizures are the most common type of seizures observed in the pediatric age group.

Evidence suggests, however, that they have little connection with cognitive function, so the prognosis for normal neurological function is excellent in children with febrile seizures. In 1980, a consensus conference held by the National Institutes of Health described a febrile seizure as, “An event in infancy or childhood usually occurring between six months and five years of age, associated with fever, but without evidence of intracranial infection or defined cause " Children with febrile seizures have a slightly higher incidence of epilepsy compared with the general population (2% vs 1%). Risk factors for epilepsy later in life include complex febrile seizure, family history of epilepsy or neurologic abnormality, and developmental delay. Febrile seizures are divided into 2 types: simple febrile seizures (which are generalized, last < 15 min and do not recur within 24 h) and complex febrile seizures (which are prolonged, recur more than once in 24 h, or are focal). Clinicians evaluating infants or young children after a simple febrile seizure should direct their attention toward identifying the cause of the child's fever. Meningitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any febrile child, and lumbar puncture should be performed if there are clinical signs or symptoms of concern. For any infant between 6 and 12 months of age who presents with a seizure and fever, a lumbar puncture is an option when the child is considered deficient in Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) or Streptococcus pneumoniae immunizations (ie, has not received scheduled immunizations as recommended), or when immunization status cannot be determined, because of an increased risk of bacterial meningitis. A lumbar puncture is an option for children who are pretreated with antibiotics. In general, a simple febrile seizure does not usually require further evaluation, specifically electroencephalography, blood studies, or neuroimaging. The prophylactic treatment of simple febrile seizures does not need. Keywords:

febrile seizures, neuroimaging, electroencephalography

Febrile seizures in children are the most common convulsive syndrome of childhood and occur only in connection with febrile fever in children aged 6 months to 5 years (approximately 2-5% of the European and American pediatric population and up to 8% in the Japanese) Studies conducted prove that they do not affect cognitive functions and have a generally good prognosis [1]. Febrile seizures (FS) are divided into three groups: - simple FS - complex FS - symptomatic FS

Epidemiology.

Approximately 70-75% of children with FS have only simple FS, another 20-25% have complex FS and 5% have symptomatic FS. Children with simple FS are at increased risk of recurrent febrile seizures; this occurs in about one third of cases. Children younger than 12 months at the time of their first episode of simple FS have a 50% chance of having them recur, and after 12 months this chance decreases to 30%. Children who have simple PS are at increased risk of subsequently developing epilepsy. The incidence of epilepsy in these children by age 25 years is approximately 2.4%, which is approximately twice the risk in the general population. The literature does not support the hypothesis that simple PS reduces intelligence (i.e., causes learning disabilities) or is associated with increased mortality [1]. Boys are significantly more likely to have PS (the exact frequency is not determined).

Etiology of simple FS:

It is based on the hereditary factor-gene PS on chromosomes 19p and 8q13-21 [2]. In different families, the modes of inheritance vary; in some families, this is the AD type of inheritance, and there may be a multifactorial variant.

Pathophysiology of febrile seizures.

FS most often occurs in young children, because their brain has a low seizure threshold at this age. In addition, at this age, children are more often susceptible to infections such as otitis media, upper respiratory tract infections, etc., to which they respond with febrile fever. Animal studies have shown an association between endogenous pyrogens, such as interleukin 1 beta, and increased neuronal excitability [5]. Also, ongoing studies show that in children the cytokine network is activated and plays a role in the pathogenesis of FS, but its exact clinical pathophysiological role is not yet clear [6, 7]. The risk of recurrence of FS

is higher in children who: - are younger than 15 months - have frequent fevers - whose parents and siblings had FS or epilepsy - had a short interval between the onset of fever and the onset of FS - had a low-grade fever before the onset of seizures - risk of FS in the child's siblings with FS about 10-20% and higher if parents also had FS [10, 18].

Clinical picture of febrile seizures.

Febrile convulsions are provoked by an increase in temperature of more than 38 ° C. Moreover, the temperature threshold that can provoke FS is unique for each child. Seizures can occur within the first 24 hours after the onset of the disease (in 25-50% of children, FS may be its first symptom) [3]. Seizures are accompanied by fever (before, during or after) without any: signs of infection NS metabolic disorders history of previous seizure disorders

Clinical picture of simple FS:

- established fever in a child in the age group 3 months-5 years - a single febrile seizure lasting no more than 15 minutes (usually 2 minutes or less) over a 24-hour period - the child does not have neurological impairment on neurological examination or according to the life and developmental history -seizures and fever are not symptoms of meningitis, encephalitis, or another condition affecting the brain -seizures are described as generalized tonic or tonic-clonic -the child does not have afebrile seizures -if there is onset of seizures in one limb or there is post-seizure weakness in one limb , then this excludes simple FS - after an attack, the child might somewhat confused or drowsy, but does not have weakness in the limbs after the seizures [8].

Clinical picture of complex FS:

— Age, neurological status, life history and fever, the same as for simple FS — Seizures are either focal or prolonged (> 15 minutes, series can be 30 minutes or >) — Or several convulsive paroxysms in a row over a 24-hour period — U the child may experience temporary weakness in the extremities in which there were convulsions

Symptomatic febrile seizures:

— Age, neurological status, life history and fever, the same as for simple FS — Child already has neurological impairment or acute illness

Diagnostics.

A thorough physical examination is necessary to assess the neurological status and psychomotor and speech development. It is necessary to exclude the presence of meningeal signs, symptoms of encephalitis, meningitis, etc. in the child.

Diagnosis of simple FS.

For simple PS there are no specific laboratory and instrumental studies [12]. First of all, it is necessary to find the cause of the feverish state. If some underlying disease is suspected, laboratory tests (eg, blood electrolytes for severe diarrhea, etc.) may be ordered. A general blood test is performed if necessary, to exclude infections and according to the child’s condition upon admission to the hospital. A general urine test is performed in patients without an obvious source of infection. In most cases, serum calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, electrolytes, and TBC levels are not indicated (Level of Evidence: B). Diagnostic lumbar puncture is mandatory for children under 12 months of age, and according to indications for children under 18 months of age. If the child received antibiotics before the onset of seizures, they may improve the symptoms of meningitis, and lumbar puncture is warranted in this situation regardless of age (Evidence Level D) [15]. If a child has meningeal signs, a lumbar puncture is mandatory (level of evidence B). In children aged 6 to 12 months who have not been fully vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae type B and pneumococcus or their vaccination history is unknown, puncture is also indicated (level of evidence D) [16].

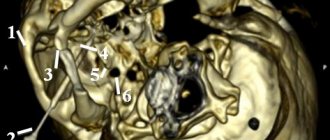

Neuroimaging in febrile seizures.

In simple PS, CT and MRI of the brain are not indicated (level of evidence B) [4, 8]. If a child has focal neurological symptoms, neurocutaneous signs, macro- and microcephaly, if neurodeficiency persists for several hours after PS, as well as with repeated complex PS, neuroimaging is performed [8]. It is also necessary if there is any doubt that these seizures are febrile in nature. Preference should be given to MRI rather than MSCT, as a more sensitive, informative and safe research method for children [17, 20].

Electroencephalography for febrile seizures.

EEG is not useful in prognostic terms in children with FS (level of evidence B). At the same time, epileptiform activity is often recorded during a continuous EEG (necessarily with recording of the sleep period). In addition, EEG has low sensitivity in children under 3 years of age (and routine EEG is practically useless). EEG also plays a limited role in the diagnosis of acute encephalopathies [18, 20].

Differential diagnosis for FS.

It is carried out with the following conditions: - Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis - Ischemic stroke - Thrombosis of the basilar artery - Idiopathic focal epilepsies of childhood - Meningococcal meningitis - Focal and generalized epilepsies - Neonatal meningitis - Viral encephalitis and meningitis

Treatment of febrile seizures.

Most simple FS goes away on its own, self-limiting, even before the patient is taken to the hospital. If the seizures are not stopped, the administration of benzodiazepines would be justified. Unfortunately, in Russia there are no the most effective and safe drugs to use: buccal midazolam, rectal diazepam, injectable lorazepam. Rectal diazepam (0.5 mg/kg) or lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg) should be administered if intravenous access cannot be established quickly [9]. Buccal midazolam (0.5 mg/kg; max dose 10 mg) was more effective than rectal diazepam in children [13]. Intravenous lorazepam is at least as effective as intravenous diazepam but is associated with fewer side effects (including respiratory depression) in the treatment of acute clonic and tonic-clonic seizures.

Preventive treatment of febrile seizures.

Continuous daily AC therapy can be carried out with phenobarbital and valproic acid drugs, but the side effects of drugs (phenobarbitalone on cognitive function, valproic acid on the liver and coagulation system) with a fairly favorable prognosis of FS are not justified [19, 20]. It is recommended to avoid continuous prophylactic administration of ACs for simple FS. In complex PS, the risks of therapy and the risks of recurrence of attacks, as well as further development of epilepsy, must be carefully weighed

Indications for hospitalization for febrile seizures.

— Undifferentiated infection — Severe infection requiring hospitalization — Repeated FS, complex FS — High degree of anxiety for parents and guardians

Consulting parents.

Febrile seizures cause great fear and anxiety in parents, so first of all, they need to be reassured and explained, most often, the benign prognosis for this condition. It is also necessary to explain to them how to behave during seizures and what help to provide to the child. It is also necessary to inform them about possible relapses of these conditions and, if the convulsions last more than 10 minutes, deliver the child by ambulance or your own transport to the nearest hospital. Febrile seizures are recognized as a benign syndrome, determined mainly by genetic factors and manifested by an age-related readiness to seizures, which eventually disappears with age. Long-term management of febrile seizures should focus on reducing parental anxiety. Long-term preventive treatment is recommended only for a small number of children with FS.

For correspondence

Lyukshina Natalya Gennadievna - Candidate of Medical Sciences, doctor of the highest category, head of the neurological department and head of the city epileptology department, member of the European Society of Child Neurologists, member of the International Association of Child Neurologists. e-mail

Diagnosis of febrile seizures

The diagnosis of AF is exclusively clinical: establishing the presence of epileptic seizures against the background of elevated body temperature in children under 6 years of age. The main difficulty that requires increased attention from doctors to this problem is the exclusion of other diseases (primarily intracranial infections), as well as HHE and DESC syndromes.

Most neurologists recommend hospitalization for the first episode of AF (9). It is necessary to carry out diagnostic measures to exclude neuroinfection (meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess). It is known, for example, that herpetic encephalitis can debut with generalized convulsive attacks at high temperatures. The slightest doctor’s suspicion of a neuroinfection, as well as such signs as prolonged AF, serial attacks, comatose state of the patient, persistent hyperthermia to high levels, require a spinal puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

An EEG study, as well as long-term video-EEG monitoring with the inclusion of sleep, play a minor role in the diagnosis of febrile attacks themselves. At the same time, they are important for excluding epilepsy, especially studies over time. EEG examination in the interictal period with typical FS does not differ from the norm (8). Some authors note an increased frequency of detection of hypnagogic hypersynchronization, which is not a reliable criterion (5).

In atypical AF, continued regional slowing (usually in one of the temporal leads) may be detected (11). With febrile seizures plus syndrome, short diffuse discharges of peak wave activity in the background are often detected.

What are febrile seizures?

Cramps are involuntary muscle contractions. Febrile convulsions begin suddenly: except for a high temperature, nothing predicts them - the child has just been playing or, for example, walking from room to room, and suddenly his eyes roll back, his head throws back, his arms and legs cramp, his lips turn blue, his teeth clench... And the convulsion can capture both all muscles and individual groups of them. During convulsions, vomiting, involuntary separation of urine and feces are possible.

The attack lasts from a few seconds to 15 minutes. After it, the child seems to be stunned and usually quickly falls asleep.

Approaches to the prevention of febrile seizures

The possibility of recurrence of febrile seizures, as well as the risk of their transformation into afebrile ones, determines the need to develop special tactics. In everyday practice, the doctor is faced with the choice of the following methodological techniques: long-term (3-5 years) therapy, intermittent therapy (during the probable risk of developing febrile seizures), refusal of any prophylaxis.

As a rule, prophylactic treatment with anticonvulsants is recommended only in cases where the child has a condition other than simple febrile seizures. In this case, there are recommendations:

- children with neurological impairment and developmental delay should be considered as candidates for prophylactic treatment with anticonvulsants;

- if the first febrile attack was complex (multiple, prolonged or focal convulsions) and after it there was a rapid and complete normalization of the child’s condition, treatment is not indicated, except in cases where a positive family history of non-febrile convulsive attacks has been established;

- a positive family history of simple febrile seizures serves as a relative contraindication to therapy in the above situations;

- Children with frequent and prolonged febrile seizures require treatment. (2)

conclusions

Dispensary observation of children who have suffered febrile convulsions is carried out by a pediatrician and a neurologist. The main tasks of specialists are the correct diagnosis of febrile seizures, conducting additional examinations, determining indications for hospitalization, treatment tactics and prevention of repeated febrile paroxysms. When the first attack of febrile seizures occurs, it is very important to classify them into simple and complex, which is of fundamental importance for the prognosis. In some cases, children with febrile seizures have to be hospitalized. Children who have had febrile seizures should be followed up by a neurologist: after 1 month. after an attack of febrile seizures, then 2 times a year. An electroencephalographic study is carried out after an attack of febrile seizures, then once a year.

Dispensary observation allows in many cases to avoid the recurrence of convulsive paroxysms, promptly exclude organic pathology of the central nervous system, and prevent the side effects of the anticonvulsant drugs used.

The most important task of a doctor, in addition to correctly establishing a diagnosis and prescribing adequate therapy, is to advise parents. The family's first reaction to a diagnosis of febrile seizures or seizure disorder is usually accompanied by a sense of grief and loss of a previously healthy child. The thought of febrile seizures turning into epilepsy, a condition that is never completely cured, can make a family miserable. When the first episode of febrile seizures occurs, the doctor should explain to the parents the rules of first aid, discuss the possible causes of the development of febrile seizures, the likelihood of recurrence of attacks, the possibility of “transition” of febrile seizures into epilepsy, emphasizing the relatively low (4%) degree of risk and favorable prognosis of febrile seizures.

Cooperation between the doctor and parents is the key to successful treatment and further development of the child. It is no coincidence that one of the founders of modern epileptology, Professor Lennox, wrote: “A good doctor deals not only with turbulent waves in the brain, but also with upset feelings, unbridled emotions, since a patient with epilepsy is not just a neuromuscular drug, he is, first of all, personality is an integrated combination of physical, mental, social and spiritual qualities. Neglect of each of them leads to deterioration and aggravation of the disease...”

References

- Ternkin O.The falling sicknes, a history of epilepsy from the Greeks to the beginning of modern neurology. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press 1924.

- Fenichel J.M. Pediatric neurology: Fundamentals of clinical diagnosis: Translated from English. — M.: OJSC “Publishing House “Medicine”, 2004 — 640 p.

- Hauser WA The prevalence and incidence of convulsive disorders in children // Epilepsia. - 1994. - V. 35 (Suppl 2). — P. 1–6.

- Tsuboi T. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy in Tokyo // Epilepsia. - 1988. - V. 29 (2). — P. 103–110.

- Panayiotopoulos CP The epilepsies: Seizures, Syndromes and Management. - Bladon Medical Publishing, 2005. - 417 p.

- K.Yu. Mukhin, M.B. Mironov, A.F. Dolinina, A.S. Petrukhin, FEBRILE SEIZURES (LECTURE), Rus. zhur. det. neuro.: vol. V, issue. 2, 2010, p 17-30

- Baram TZ, Shinnar Sh. Febrile seizures. - Academic Press, Orlando, 2002. - 337 p.

- Mukhin K. Yu., Petrukhin A. S., Mironov M. B. Epileptic syndromes. Diagnostics and therapy (reference guide for doctors) // M.: System solutions, 2008. - 224 p.

- Badalyan L. O., Temin P. A., Mukhin K. Yu. Febrile seizures: diagnosis, treatment, follow-up // Methodological recommendations. - Moscow, 1988. - 24 p.

- Sadler RM The syndrome of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis: clinical features and differential diagnosis // In: Advances in neurology. - V. 97. - Intractable epilepsies. Eds.: WT Blume / Lippincott, Philadelphia, 2006. - P. 27–37.

- Mukhin K. Yu., Petrukhin A. S. Idiopathic forms of epilepsy: systematics, diagnosis, therapy. - M.: Art-Business Center, 2000. - 320 p.

Pediatrician, doctor of the highest category, neurologist I. E. Tambiev. I. G. Kovalev.

Convulsions in children at high temperatures

Convulsions in children occur when body temperature rises above 38 ºС during an infectious disease (acute respiratory diseases, influenza, otitis media, pneumonia, etc.).

What is typical for seizures due to fever?

Usually observed at a height of temperature and stop when it drops, they do not last long - from several seconds to several minutes; in addition, the child may lose consciousness.

How to help a child with seizures

- Lay the patient down, turn his head to the side, provide access to fresh air; restore breathing: clear the mouth and throat of mucus.

- Carry out antipyretic measures. If the child has a pronounced fever, that is, the skin is hot to the touch and has a reddish tint, then you can use:

- blowing with a fan (with caution);

- a cool, wet bandage on the forehead;

- cold on the area of large vessels (armpits, groin area);

- carry out wiping - 40% alcohol, 9% (!) table vinegar, water mixed in equal volumes (1:1:1). You can simply use alcohol with water or 9% vinegar with water in equal parts. Wipe with a cotton swab soaked in this solution (except for the face, nipples, genitals), then allow the child to dry; repeat

Take paracetamol (acetaminophen, Panadol, Calpol) in a dose of the child's weight at a time or ibuprofen weight (for children over 1 year).

If a child has a background of elevated temperature: pale skin, a bluish tint to the lips and nails, cold palms and feet, chills, then wiping and other cooling measures cannot be carried out. It is necessary to warm the child and, against the background of antipyretic therapy, give no-shpa or papaverine at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight orally (to dilate blood vessels).

What are they and why do they occur?

Reasons for febrile seizures in children. Febrile seizures are involuntary muscle contractions of the limbs, neck or entire torso, varying in duration, intensity and location.

Febrile seizures

In very young children they can be congenital, including hereditary, associated with diseases of the nervous system, intrauterine infections, and birth injuries.

But most often, seizures in infants are caused by high body temperature - these are febrile seizures.

This reaction to high temperature is associated with the physiological characteristics of the brain of a small child - instability of the processes of excitation and inhibition, increased permeability of blood vessels.

The decisive factor in this case is not how high the temperature is, but how quickly it rises.

As a rule, high fever with convulsions occurs with influenza, rubella, chicken pox, meningococcal infection and scarlet fever.