Vegetative-vascular dystonia (VSD) - symptoms and treatment

All therapeutic measures for VSD include an impact on etiological factors and pathogenesis links, as well as general strengthening measures.

The impact on the causes of the disease is the desire to normalize lifestyle and eliminate the influence of pathogenic factors on the body.

Which doctor should I contact?

If symptoms of autonomic dysfunction of the nervous system appear, you should consult a neurologist.

Treatment of VSD, based on its pathogenesis , involves:

- normalization of cortical-hypothalamic and hypothalamic-visceral connections with the help of sedatives, tranquilizers, antidepressants and minor neuroleptics [10];

- reducing the activity of the sympathetic-adrenal system and reducing the clinical effects of hypercatecholaminemia through the use of beta-blockers.

When normalizing the afferent connections of the hypothalamus, it is preferable to use high-potential benzodiazepines (alprazolam, lorazepam, phenazepam), but only for a short course, and only to relieve “acute anxiety”, since a dependence syndrome quickly forms, and with prolonged use a withdrawal syndrome may occur. Phenazepam is also practical due to its lower toxicity (2.5 times less toxic than diazepam). Of the antidepressants in modern practice, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are more often used, since it is the lack of these neurotransmitters that causes the development of psycho-vegetative disorders [19]. Of the “small” antipsychotics, sonapax (thioridazine), eglonil (sulpiride) and teraligen (alimemazine) have found their use in neurological practice, since, having an “antipsychotic” effect, they are not accompanied by pronounced side effects of “larger neuroleptics” - extrapyramidal syndrome, hypersalivation and others [3].

Also, when approaching the treatment of vegetative-vascular dystonia from the point of view of pathogenesis, to correct neurotransmitter disorders, it is necessary to use drugs that restore cerebral metabolism:

- nootropics (glycine, phenibut);

- vitamin preparations - B vitamins (most often in medical practice complex forms are used - combilipen and milgamma - the main participants in the transmission of nerve impulses and myelin synthesis), as well as vitamins with antioxidant effects, especially A, E, C [9];

- ascorbic acid - activates redox reactions, increases the adaptive capabilities of the body [6][14].

To normalize metabolism, metabolic drugs (riboxin, mildronate) are actively used, which also have a microcirculatory, antihypoxic effect, normalizing glucose metabolism and oxygen transport [5].

General restorative measures for VSD include the elimination of alcohol, nicotine, coffee, a healthy diet, normalization of sleep, exercise therapy (physical therapy), and sanatorium-resort treatment [5]. Therapeutic massage, reflexology and water treatments also have a positive effect. The choice of physiotherapeutic treatment is influenced by the type of VSD: electrophoresis with calcium, mesatone and caffeine for vagotonia, electrophoresis with papaverine, aminophylline, bromine and magnesium for sympathicotonia [12].

psychotherapy is also very important in the treatment of VSD , during which the patient is explained the nature of the disease, is convinced that the disease is not life-threatening and has a favorable outcome, and skills are developed to control the psychosomatic manifestations of the disease and adequately respond to them [3 ].

The domestic drug Mexidol (ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate) also occupies a strong position in the complex treatment of VSD due to its antioxidant, microcirculatory, metabolic and, importantly, anxiolytic properties. By modulating the activity of receptor complexes, it preserves the structural and functional organization of biomembranes, transports neurotransmitters and improves synaptic transmission [14].

Recently, neurotrophics - cereton (choline alfoscerate), cortexin and cerebrolysin - have been very actively used in the practice of neurologists in the correction of autonomic disorders to strengthen the neurointegrative functional connections of various parts of the nervous system with each other and with underlying organ systems [3].

If cardiovascular syndrome predominates in the VSD clinic, in complex therapy with beta blockers for tachycardias and extrasystoles, potassium and magnesium preparations are used - asparkam (Panagin) and magne B6 (Magnelis) [14]. For vagotonia, use calcium supplements [4].

If headaches, weakness, dizziness and other cerebrovascular disorders against the background of sympathicotonia are expressed during VSD, then vasodilators (for example, myotropic antispasmodics) and vasocorrectors with a vasodilating effect (Cavinton, pentoxifylline) are used, which not only improve cerebral circulation, but also cerebral metabolism by improving oxygen transport, reducing hypoxia and glucose processing [3][9][14]. If cerebrovascular disorders occur within the framework of parasympathicotonia with a decrease in blood pressure, then drugs that stimulate vascular tone (vasobral) are more preferable. Nootropics can be used for the same purpose, as they stimulate the cardiovascular center of the nervous system.

In the case of intracranial hypertension syndrome, which is most often represented in VSD by functional cerebrospinal fluid-dynamic disorders, mild dehydration therapy (acetazolamide, furosemide in combination with potassium supplements) will contribute to improvement. Long-term use of diuretic herbs is also recommended [9].

In case of VSD, chronic foci of infection are treated with concomitant strengthening of the immune system using various immunostimulants (immunal, wobenzym, polyoxidonium) [3].

Psychovegetative syndrome

It is a set of syndromes caused by disturbances in the mechanisms of autonomic regulation. The list of symptoms is quite impressive, but the most common are fluctuations in blood pressure, pulse and respiration rates, disturbances in thermoregulation (low-grade fever, decreased body temperature), muscle tone, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, urinary retention, hyperhidrosis, dry mouth, hypersalivation, tearfulness, mydriasis, exophthalmos. Patients often complain of suffocation, a feeling of shortness of breath, a feeling of lack of air, and heart rhythm disturbances. Their anxiety is also associated with a feeling of heaviness in the epigastric region, a feeling of fullness in the stomach, flatulence, and belching.

| | In order to determine psychovegetative syndrome, it is necessary to undergo diagnostics |

Autonomic disorders can be diffuse, as well as local: cardioneurosis, angioneurosis, hyperventilation syndrome, irritable stomach, intestinal syndromes, etc. These are the so-called organ neuroses.

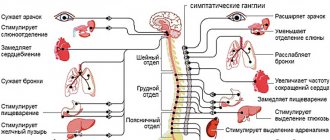

Autonomic disorders can be permanent, but often, especially at the beginning of the disease, they occur in the form of paroxysms that last up to two to three hours or more. Such attacks are sometimes identified with panic attacks, which requires solid evidence. The clinical structure of the psychovegetative syndrome may reflect the predominance of sympathetic tone (tachycardia, tendency to arterial hypertension, atonic constipation, mydriasis, exophthalmos, low-grade fever, dry mouth, hyperhidrosis) - a phenomenon of ergotrophic adjustment. In other cases, vagoinsular innervation dominates: nausea, vomiting, loose and frequent stools, rapid diuresis, arterial hypotension, hypersalivation, hypothermia, bradycardia, a feeling of suffocation - the phenomenon of trophotrophic adjustment. Mixed, amphitonic states are often encountered.

In child psychopathology, the term neuropathic syndrome is used, which means not only autonomic disorders, but also disorders of general activity, sleep, thermoregulation, appetite, regurgitation, vomiting, mood disorders, and physical development (hypotrophy). Neuropathic syndrome in children aged 2–3 years can manifest itself as affective respiratory attacks. Children, according to the stories of relatives, “roll up” and “get into trouble.” During crying, spasm of the laryngeal muscles, respiratory arrest, and asphyxia occur. The skin turns blue, consciousness darkens, and tonic convulsions develop. Catamnesis of children with affective-respiratory convulsions, as well as febrile seizures, indicates that a significant proportion of patients subsequently experience epilepsy. Neuropathic syndrome is considered typical for children under three years of age suffering from various diseases.

Psychovegetative syndrome is a nonspecific disorder.

It occurs in all mental illnesses; in the early stages of development it can be their main manifestation. Back to contents

Effective therapy of psychovegetative disorders in neurology

In his clinical practice, a neurologist often encounters disorders caused primarily by psychogenic factors. Their clinical picture can be very diverse - patients may notice episodic or chronic headaches, dizziness, weakness and fatigue, sleep disturbances, shortness of breath, sweating, pain in the chest, interruptions in heart function, dyspepsia... If certain complaints are dominant, the diagnosis may formulated as “tension headache” or “hyperventilation syndrome”, “conversion hysteria” or “depression”1. Also A.M. Wayne and his co-authors proved2 that in such patients, emotional and affective disorders (anxiety, depressive, hypochondriacal, etc.) may be hidden behind vivid vegetative-somatic complaints. Modern neurology gives these clinical forms a common name - “psychovegetative syndrome.”

Psychovegetative syndrome (PVS) can be the first sign or accompany various somatic and neurological diseases: vascular, degenerative diseases of the central nervous system, neuropathies, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, etc. Moreover, it is often the severity of PVS, and not the symptoms of the underlying disease, that determines the severity of the patient’s condition and his quality of life. That is why the success of treatment as a whole, and sometimes the prognosis of life, depends on the effectiveness of PVS therapy.

Difficulties in treating psychovegetative syndrome

Selecting an adequate drug for the treatment of PVS can be difficult for a neurologist for objective reasons: patients may refuse to recognize the emotional component of their illness and take antidepressants. In addition, the delayed effect (3-4 weeks) of these drugs often forces the patient to quit therapy without waiting for the result, which leads to chronicity of the disease and undermining trust in the doctor and treatment as such.

The main medications for the treatment of patients with complex psychogenic symptoms are vascular, metabolic, nootropic and vitamin drugs. The use of psychotropic drugs, in particular tranquilizers from the benzodiazepine group, is also indicated, but is very limited due to their serious side effects, the most unpleasant of which, perhaps, are:

- hypersedation, or “behavioral toxicity”;

- addiction and dependence;

- phenomena of withdrawal and recoil.

Thus, seduxen, phenazepam, clonazepam, alprazolam and other typical benzodiazepines can cause dependence with long-term use, after discharge from the hospital, and with abrupt withdrawal they are fraught with exacerbation of symptoms.

In Russia, benzodiazepines are quite popular. While in world practice, they try to avoid the use of benzodiazepines not only for a course of treatment, but also for the treatment of acute stress. The World Health Organization, in its recommendations for PTSD, strictly does not recommend resorting to benzodiazepines after a traumatic event for a month, as this slows down the recovery period.

In connection with these circumstances, today it is extremely important to search for a drug that effectively relieves psychovegetative disorders, but does not have the classic disadvantages of benzodiazepines3. The atypical tranquilizer Grandaxin can serve as such a drug.

Grandaxin. Mechanism of action and benefits of the drug

Grandaxin (tofisopam) was produced by the Hungarian pharmaceutical plant EGIS4 in the mid-70s.

The main feature of tofisopam, which determines its unique properties, is the location of the nitrogen group. If in traditional benzodiazepines it is located in positions 1–4, then in tofisopam it is located in positions 2–3. The action of Grandaxin, like all benzodiazepine tranquilizers, is based on increasing the affinity of GABA, a nonspecific inhibitory transmitter, to the receptor. This causes a wide range of inhibitory effects both on the emotional sphere (reducing anxiety and restlessness) and on the vegetative functions of the body (vegetative stabilizing effect). At the same time, being an atypical 2-3 tranquilizer, tofisopam has the following properties, thanks to which it has such a wide range of applications:

- physical dependence does not develop to it;

- it does not have sedative and muscle relaxant effects;

- does not potentiate the effect of alcohol;

- does not impair attention, memory and other cognitive functions;

- does not have a cardiotoxic effect (on the contrary, its beneficial effect on coronary blood flow and myocardial oxygen demand has been proven);

- has a moderate stimulating effect (due to which it was classified as a “daytime” tranquilizer that can be taken at any time of the day) 5.

Today Grandaxin is actively used by neurologists and general practitioners. In particular, it is prescribed for psychovegetative disorders of neurotic origin6 (especially those accompanying anxiety), when combined with cerebrovascular diseases, including in elderly patients with somatic and cognitive disorders. In outpatient practice, it is used in the treatment of stress disorders and adaptation disorders. Grandaxin is also used in gynecology to treat menopause and premenstrual syndrome, as well as to relieve anxiety and improve the quality of life in chronic somatic diseases. The mildness of the drug’s action allows it to be prescribed to active patients who need to continue treatment without interrupting their professional activities, and the favorable tolerability profile allows one not to be afraid of serious side effects and to avoid regular monitoring of physiological parameters.

Proof of clinical effectiveness

The effectiveness of Grandaxin is regularly tested using multicenter placebo-controlled studies. Thus, in a recent work devoted to the use of the drug in neurological practice, carried out by G.M. Dyukova, E.V. Saxonova, V.L. Golubev et al.7 involved 220 patients with psychovegetative syndrome. Their official diagnoses ranged from autonomic nervous system disorder, neurotic and somatoform disorder, adjustment disorder, to anxiety disorder, and emotional disturbances.

In 35% of patients, along with PVS, other diseases were diagnosed (dyscirculatory encephalopathy, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, migraine without aura, cervicalgia and lumbodynia), and 65% had only PVS in the clinical picture.

The study made it possible to establish that the addition of Grandaxin to the standard therapy of patients with PVS with nootropic, metabolic and vascular drugs allowed a significantly faster and more significant improvement in the condition of patients. Based on the results of the tests, the psycho-vegetative imbalance was normalized, and the quality of sleep improved. Patients with insomnia disorders especially noted the effectiveness of the drug.

Grandaxin significantly improved the physical performance and quality of life of patients. The good tolerability of the drug and the reduction of possible adverse events during treatment make it possible to recommend it to patients with both a psychovegetative symptom complex and concomitant somatic and neurological pathologies.

Other studies have shown the effectiveness of using Grandaxin not only for permanent anxiety disorders (which occur as PVS), but also for paroxysmal anxiety (“panic attacks” or “vegetative crises”)8. The use of tranquilizers is recommended:

- as an adjuvant to accelerate the clinical effect;

- to enhance the effect when the dose of an antidepressant is limited by side effects;

- for the correction of anxiety and panic disorders, the intensification of which is provoked by the start of taking antidepressants.

Thus, Grandaxin can be called an indispensable element in complex therapy in patients with both leading and concomitant PVS in chronic neurological diseases (vascular, degenerative, demyelinating, etc.).

Grandaxin differs from typical benzodiazepines in its structure, which determines the difference in pharmacological action. This drug, like typical benzodiazepines, has an anxiolytic effect, however, it does not cause sedation, muscle relaxation, or hypnotic effect.

An extremely important point is the early onset of the positive effect of treatment, compared to classic benzodiazepines (already in the 2nd week), which increases the patient’s faith in recovery.

Grandaxin is a fast daytime anxiolytic and vegetative corrector. It significantly reduces the severity of emotional disorders, stabilizes the functioning of the nervous system, and helps restore full, sound sleep. The safety of the drug and its good tolerability make it possible to unambiguously define it as a basic component of the treatment regimen for a significant part of neurological patients.

1 Perkin G. An analysis of 7836 successful new outpatient referrals. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat 1989;52:447-448. 2 Wayne A.M. (ed.) Autonomic disorders. Clinic, diagnosis, treatment. M 1998; 752. 3 Dyukova G.M. Grandaxin in clinical practice. Treat Nerv Diseases 2005;2:16:25–29. Lawrence D.R., Benitt P.N. Clinical pharmacology. Volume 2. M: Medicine1991; 700. Mierzejewski S., Dabrowski R. Anxiolytics (benzodiazepine derivatives). News Pharmac Med 1994;4:71-76. Mosolov S.N. Fundamentals of psychopharmacology. M: Vostok 1996; 288. 4 Ronai S., Oros F., Bolla K. Use of Grandaxin in outpatient practice. Wenger Pharmacoter 1975;23:4-10. Szegi J., Somogyi M., Papp E. Excerpts from the clinical-pharmacologic and clinical studies of Grandaxin. Acta Pharm Hung 1993;63:2:91-98. 5 Bond A., Lader MA Comparison of the psychotropic profiles of tofisopam and diazepam. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1982;22:2:137-142. 6 Artemenko A.R., Oknin V.Yu. Grandaxin in the treatment of psychovegetative disorders. Treat Nerv Diseases 2001;2:1:24-27. 7 Dyukova G.M., Saxonova E.V., Golubev V.L. Grandaxin in neurological practice (Multicenter study). Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry 2009;9:44-48 8 Vein A.M., Dyukova G.M., Vorobyova O.V., Danilov A.B. Panic attacks (neurological and psychophysiological aspects). 1997 St. Petersburg. P.304. Djukova GM, Shepeleva JP, Vorob'eva OB Treatment of vegetative crises (panic attacks). Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology. 1992. V.22. No. 4. R.343-345. Sheehan DV Raj A: Benzodiazepine treatment of panic disorder. In: Handbook of anxiety. Elsevier. Amsterdam. 1990. R.169-206.

O.V. Kotova Department of Pathology of the Autonomic Nervous System, Research Center of the First Moscow State Medical University named after. I.M.Sechenova

The principles of diagnosis and treatment of psychovegetative syndrome are considered. An integrated approach significantly improves treatment results: it is advisable to combine any psychotropic drugs with vegetotropic therapy. Key words: psychovegetative syndrome, psychotropic drugs, vegetotropic therapy, ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate. Possibilities of treatment of psychovegetative syndrome OVKotova First Moscow Medical State University named by IMSechenov, Moscow

Principles of diagnosis and treatment of psychovegetative syndrome are considered. Complex approach may significantly improve results of treatment: it is reasonable to combine any psychotropic medications with vegetotropic therapy. Key words: psychovegetative syndrome, psychotropic medications, vegetotropic therapy, ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate.

Information about the author: Olga Vladimirovna Kotova – Candidate of Medical Sciences, senior researcher at the Department of Nervous Diseases of the First Moscow State Medical University

Autonomic dystonia syndrome (VDS) is a diagnosis made by doctors of various specialties to a huge number of patients. Unfortunately, doctors often forget that SVD is a combination of several clinical units, namely:

• psychovegetative syndrome (PVS) – the most common form of SVD; • peripheral autonomic failure syndrome; • angiotrophoalgic syndrome.

This article will focus primarily on PVS. In the middle of the last century, the German researcher W. Thiele proposed the term “psychovegetative syndrome” to refer to suprasegmental autonomic disorders. In Russian literature, this term was established thanks to the works of Academician A.M. Wayne, and is still used to designate SVD associated with psychogenic factors and as a manifestation of emotional and affective disorders [1]. According to statistics, more than 25% of patients in the general somatic network have PVS. In certain territories of Russia, the volume of the diagnosis of SVD is 20-30% of the total volume of registered data on morbidity, and in the absence of the need to refer the patient for consultation to specialized psychiatric institutions, it is coded by doctors and statisticians of outpatient clinics as a somatic diagnosis [2, 3]. In more than 70% of cases, SVD is included in the main diagnosis under the heading of somatic nosology G90.9 - disorder of the autonomic (autonomic) nervous system, unspecified or G90.8 - other disorders of the nervous system. According to the results of a survey of 206 neurologists and therapists in Russia, participants in conferences held by the Department of Pathology of the Autonomic Nervous System of the Scientific Research Center and the Department of Nervous Diseases of the First Moscow State Medical University named after I.M. Sechenov for the period 2009-2010, 97% of respondents use the diagnosis “SVD” in their practice, of which 64% use it constantly and often [3]. Despite the fact that PVS is not an independent nosological entity, most doctors use this term for a syndromic description of psychogenically caused multisystem autonomic disorders. The latter include disorders of somatic (autonomic) functions of various origins and manifestations, associated with a disorder of their neurogenic regulation. Therefore, the terms “neurocirculatory dystonia” or “vegetative-vascular dystonia” are a special case of PVS and indicate autonomic disorders with an emphasis on disorders in the cardiovascular system [4, 5]. Most often, patients with this pathology are characterized by a high probability of repeated visits to specialists due to dissatisfaction with the prescribed treatment. When visiting a doctor, patients complain primarily of somatovegetative disorders: persistent cardialgia, prolonged and “unexplained” hyperthermia, constant shortness of breath, persistent feeling of nausea, debilitating sweating, dizziness, dramatic vegetative paroxysms for patients or, in modern terminology, “panic attacks" (PA), etc. SVD can develop as a result of many reasons and have different nosological affiliations. SVD may have a hereditary-constitutional nature. In this case, autonomic disorders debut in childhood and are often familial and hereditary in nature. With age, vegetative instability can be compensated, but this compensation is, as a rule, unstable and is disrupted under any stress (stressful situations, physical activity, changes in climatic conditions, occupational hazards, as well as a large number of internal factors - hormonal changes, somatic diseases, etc. ). SVD can occur as part of psychophysiological reactions in healthy people under the influence of extraordinary, extreme events and in an acute stressful situation. SVD can occur during periods of hormonal changes (puberty, premenopause and menopause, pregnancy, lactation), as well as when taking hormonal medications. SVD occurs in various occupational diseases, organic somatic and neurological diseases. Treatment of the underlying disease leads to a decrease or complete disappearance of signs of VDS. In the vast majority of cases, the cause of PVS is mental disorders of an anxious or anxious-depressive nature within the framework of neurotic, stress-related disorders, or, less commonly, an endogenous disease. Mental disorders - anxiety and depression, along with mental symptoms, have somatic or autonomic disorders in their clinical picture. In some patients, vegetative symptoms are leading in the clinical picture of the disease, in others, mental disorders come first, which are accompanied by pronounced vegetative disorders, but such patients consider them a natural reaction to an existing “severe somatic illness.” For this reason, patients seek help from a general practitioner, cardiologist, gastroenterologist or neurologist, which makes the problem of PVS interdisciplinary, and doctors of different specialties need not only to be able to diagnose the disease, but also to be able to help the patient get rid of his suffering [1, 6]. Analysis of the characteristics of subjective and objective somatic or vegetative manifestations helps to assume their psychosomatic or psychovegetative nature. One of the most important features of PVS is the polysystemic nature of autonomic disorders. The doctor’s ability to see, in addition to the leading complaint, the naturally accompanying disorders of other systems, allows one to understand the pathogenetic essence of these disorders already at the clinical stage. For example, cardialgia with PVS is most often associated with muscle tension in the pectoral muscles and is closely related to increased breathing and hyperventilation. Sinus tachycardia from 90 to 130-140 beats/min is a common manifestation of PVS. Subjectively, patients feel not only a rapid heartbeat, but also that the heart “hits the chest,” interruptions, tremors, and fading (extrasystoles). In addition to these cardioarrhythmic disorders, patients experience general weakness, dizziness, lack of air, and paresthesia [7]. Gastrointestinal tract (GIT) disorders of a psychogenic nature are detected in 30-60% of patients in the gastroenterology department. The most serious manifestation is abdominalgia. A feature of abdominalgia with PVS is their tendency to paroxysms, as well as strong psycho-vegetative accompaniment (hyperventilation, increased neuromuscular excitability, increased gastrointestinal motility). The presence of a certain connection between the patient’s subjective experiences, the dynamics of the psychogenic situation and the appearance or aggravation of certain somatic symptoms is one of the criteria for PVS. Reduction of somatic complaints usually occurs under the influence of sedatives - validol, corvalol, valerian, benzodiazapines, etc. Careful questioning of the patient can reveal the unusualness of clinical manifestations and dissimilarity to known somatic suffering. If there are complaints about the presence of pain - cardiagia or abdominalgia - the nature of the pain can vary widely. The pain can be stabbing, pressing, squeezing, burning or throbbing. These may also be sensations that are far from pain in their characteristics (discomfort, an unpleasant sensation of “feeling of the heart”). They may have atypical localization for organic pain and wider irradiation. For example, with cardialgia, pain radiates to the left arm, left shoulder, left hypochondrium, under the shoulder blade, in the axillary region, in some cases it can spread to the right half of the chest; it lasts longer than with angina pectoris. With abdominal pain, pain is localized, as a rule, along the midline of the abdomen. The correlation between the patient’s ideas about his illness (in patients with PVS the internal picture of the disease is “developed” and is fantastic) and the degree of their implementation in behavior allows us to determine the role of mental disorders in their pathogenesis. When examining a patient with PVS, there are no objective clinical and paraclinical signs indicating the presence of organic pathology in a particular system [8]. The differential diagnosis of SVD should be made with thyrotoxicosis, since with an increase in thyroid function, secondary anxiety disorders may appear, which have the necessary objective and subjective manifestations. The most important is the differential diagnosis of cardialgic and cardiarrhythmic syndromes with angina pectoris, especially its atypical variants, and arrhythmias. In such cases, the patient should undergo a specialized cardiac examination. This is a necessary stage in the negative diagnosis of SVD. At the same time, when examining this category of patients, it is necessary to avoid multiple, uninformative studies, since their conduct and inevitable instrumental findings can support the patient’s catastrophic ideas about his disease. It is also important to remember that manifestations of SVD in some cases may be associated with side effects of medications: amphetamines, bronchodilators, caffeine, ephedrine, levodopa, levoteroxine, antidepressants with a pronounced activating effect. When they are cancelled, autonomic disorders regress. In most cases, autonomic disorders are secondary and occur against a background of mental disorders. It must be remembered that psychovegetative syndrome is the first stage of a doctor’s diagnostic deliberations, which can be completed by making a nosological diagnosis. In this case, a psychiatrist will provide invaluable assistance to a general practitioner or neurologist by determining the type of mental disorder [9]. Currently, the following groups of drugs are used in the treatment of psychovegetative syndrome:

• vegetotropic agents; • antidepressants; • tranquilizers (benzodiazepines, typical and atypical); • minor neuroleptics.

In the treatment of PVS, given its predominantly psychogenic origin, psychotropic therapy has priority. It is not the symptom or syndrome that needs to be treated, but the disease. In the case of PVS, these are anxiety and depressive disorders [10]. It should be noted that it is advisable to combine the use of any psychotropic drugs with vegetative-tropic therapy, since an integrated approach significantly improves treatment results. Among the agents widely used for these purposes is ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate (2-ethyl-6-methyl-3-hydroxypyridine succinate) (ES), an inhibitor of free radical processes. The spectrum of action includes membrane-protective, antihypoxic, stress-protective, nootropic, antiepileptic, and anxiolytic effects. Ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate modulates the activity of membrane-bound enzymes, receptor complexes (benzodiazepine, GABA, acetylcholine), which promotes their binding to ligands, preservation of the structural and functional organization of biomembranes, transport of neurotransmitters and improvement of synaptic transmission. Although ES is not GABA, it increases the amount of this neurotransmitter in the brain and/or improves its binding to GABAA receptors [11]. ES increases the concentration of dopamine in the brain through increased activity of dopamine neurons in the central nervous system, and dopamine levels are important for emotions such as satisfaction, joy, etc. [12]. ES increases the body's resistance to the effects of various damaging factors in pathological conditions (shock, hypoxia and ischemia, cerebrovascular accidents, intoxication with ethanol and antipsychotic drugs). ES has cerebroprotective, anti-alcohol, nootropic, antihypoxic, tranquilizing, anticonvulsant, antiparkinsonian, anti-stress, vegetotropic effects. What are the indications for use: treatment of acute cerebrovascular accidents, dyscirculatory encephalopathy, psychovegetative syndrome, neurotic and neurosis-like disorders with anxiety, treatment of acute intoxication with neuroleptics and a number of other diseases. If we talk about PVS therapy, then ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate has a pronounced tranquilizing and anti-stress effect, the ability to eliminate anxiety, fear, tension, and restlessness. ES has a potentiating effect on the effects of other neuropsychotropic drugs; under its influence, the effect of tranquilizing, neuroleptic, antidepressant, hypnotics and anticonvulsants is enhanced, which makes it possible to reduce their doses and reduce side effects [13]. According to the spectrum of action, ES can be classified as a daytime tranquilizer, which is effective both in a hospital setting and in outpatient practice, while there are no sedative, muscle relaxant or amnesic effects [14]. Another equally valuable drug for the treatment of PVS, which is used as a vegetoprotector, pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is a precursor of glutamate and GABA, the main neurotransmitters in the central nervous system. Severe pyridoxine deficiency may be accompanied by the development of seizures, which usually cannot be treated with conventional means. In addition, there is increased irritability, symptoms such as dermatitis, as well as cheilosis, glossitis and stomatitis. The state of B6-dependent anxiety has been described in psychiatry [15, 16]. In his practice, a doctor always tries to choose effective drugs with a combined effect that have different points of application on the pathogenesis of the disease, as this increases the patient’s adherence to treatment. Among these drugs is MexiV 6. This is a combined drug, which is available in tablets (No. 30), contains 125 mg of ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate and 10 mg of pyridoxine, and thanks to this unique composition it has vegetotropic, anxiolytic and anti-stress effects without sedative or addictive effects, which allows you to effectively normalize the patient’s psycho-emotional background. In addition to pharmacological treatment, it is extremely important to explain to the patient the essence of the disease, and it is necessary to convince the patient that it is curable; explain the origin of symptoms, especially somatic ones, their relationship with mental disorders; convince that there is no organic disease (after a thorough examination). In addition, regular exercise, stopping smoking, and reducing coffee and alcohol consumption should be recommended.

Literature 1. Autonomic disorders/Ed. A.M.Veina. M.: 1998; 752. 2. Instructions for the use of the international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision. Approved Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation 05.25.1998 No. 2000/52-98. 3. Akarachkova E.S. On the issue of diagnosis and treatment of psychovegetative disorders in general somatic practice. Attending doctor. 2010; 10: 5-8. 4. Dyukova G.M., Vein A.M. Autonomic disorders and depression. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy. 2000; 1:2-7. 5. Smulevich A.B. Depression in general medical practice. M.: 2000; 160. 6. Vorobyova O.V., Akarachkova E.S. Herbal medicines in the prevention and treatment of psychovegetative disorders. Doctor. Special issue. 2007; 57-58. 7. Solovyova A.D., Akarachkova E.S., Toropina G.G. and others. Pathogenetic aspects of the treatment of chronic cardialgia. Journal neurol. and psychiatrist. 2007; 11 (107): 41-44. 8. Krasnov V.N., Dovzhenko T.V., Bobrov A.E. etc. Improving methods for early diagnosis of mental disorders (based on interaction with primary care specialists). Ed. V.N. Krasnova. M.: ID MEDPRACTIKA, 2008; 136. 9. Akarachkova E.S., Shvarkov S.B. Autonomic dystonia syndrome: relevance of the use of anxiolytics. Directory of a polyclinic doctor. 2007; 5 (5): 4-9. 10. Avedisova A.S. Anxiety disorders. In the book: Mental disorders in general medical practice and their treatment / Yu.A. Aleksandrovsky M.: GEOTAR-MED, 2004; 66-73. 11. Voronina T.A., Seredenin S.B. Prospects for the search for anxiolytics. Let's experiment. and wedge. pharmacology. 2002; 65 (5): 4-17. 12. Stahl SM Stahl's essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical application. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2008; 1117. 13. Kosenko V.G., Karagezyan E.A., Luneva L.V., Smolenko L.F. Application of Mexidol in psychiatric practice. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2006; 6 (106): 38-41. 14. Voronina T.A. Mexidol: main neuropsychotropic effects and mechanism of action. Pharmateka. 2009; 6:28-31. 15. Gromova O.A. Magnesium and pyridoxine: basic knowledge. M.: 2006; 223. 16. Vein A.M., Solovyova A.D., Akarachkova E.S. Treatment of hyperventilation syndrome with Magne-B6. Treatment of nervous diseases. 2003; 3 (11): 20-22.

Results and discussion

Psychovegetative symptom complex with functional paroxysmal tachycardia (PT)

We observed 15 adolescents aged 12-17 years and 10 children under 7 years old with functional P.T. It was found that children of an early age group in the pre-manifest period (before the first attack of PT) are characterized by certain distortions of early development, often in the form of asynchrony and dissociation, as well as syndromatically unformed episodic or permanent psycho-vegetative disorders. For preschool age, the most typical affective disorders are predominantly bipolar type of varying depth - from erased to typical “vital” depression and manic states (in isolated cases), as well as manifestations of affective circadianity within the framework of personality, often schizoid characteristics, with a clear predominance of the depressive pole. Depression at this age is characterized by the diversity and variability of pathological affect (a combination of hypothymia with adynamia, anxiety, fear with polythematic phobias). In a number of cases, an erased delusional component manifested itself in a complex affective (depressive or manic) syndrome. In some cases, we can talk about affective equivalents of epileptiform states, polymorphic disorders with a neurotic picture (fears, obsessions, etc.) or hallucinatory-delusional phenomena.

In the adolescent group, the polymorphism of symptoms decreased, the dominant position was occupied by depressive disorders of varying depths, but more monomorphic than in the younger age group; schizoid personality manifestations were more severe in combination with crisis-specific symptoms, which were often difficult to distinguish from symptoms of endogenous processivity. In isolated cases, symptoms characteristic of epileptiform age-related crisis or neurotic disorders were observed. In some patients, by adolescence, a distinct personality pathology develops, most often the schizothymic circle, combined with crisis-specific polymorphic disorders (fears, fluctuations in affect, behavioral deviations, etc.).

When comparing the dynamics of functional autonomic pathology and psychopathological symptoms, a clear connection was observed between the frequency and severity of cardiac arrhythmia attacks, their reduction or stabilization and fluctuations in mental status, its stabilization, transition to residual states or practical rehabilitation.

Psychovegetative symptom complex with functional hyperthermia

The group with functional hyperthermia [20] included 25 patients: 10 children under 7 years old, 15 adolescents 12-17 years old. Pre-manifest mental disorders (when manifested in the form of functional hyperthermia) were extremely polymorphic. Severe personal and behavioral deviations, and affective disorders of a situational and phase nature, and paroxysmal syndromes, and states of a neurotic type, including various, mainly motor, obsessions, were noted. The most characteristic manifestations were various fears - from situational and so-called “physiological” to clearly delusional ones with corresponding defensive behavior, illusory and hallucinatory deceptions of perception. Noteworthy is the significant frequency in the pre-manifest period of pathological sensations that are in no way related to physical diseases, which can be interpreted as senestopathies, including senestalgia. This is important, since in manifest states and subsequently it is precisely the special pathological sensations (both against the background of hyperthermia and outside of it) that are the most typical psychopathological symptoms in these patients.

In general, in the younger age group, psychopathological disorders in the manifest attack were syndromic polymorphic (adynamic or anxiety-depressive states, with and without senestopathies, fears with illusory deceptions, neurotic reactions). With age, this polymorphism increased sharply, but at the same time, the predominance of syndromes with leading senestopathic symptoms (mainly depression of various types and depressive-delusional states) was clearly revealed. In addition, various symptoms of the neurotic circle were observed, including obsessions, polymorphic schizophrenia-like hallucinatory-delusional disorders, paroxysmal states (syncopation, Kloos attacks).

In the older age group, states of asthenic failure were determined [21], which also belong to the depressive circle. But here, too, senestopathic depression prevailed, in particular depression with hypochondriacal symptoms, suicidal tendencies, and more clearly expressed ideas of relation. As a rule, autonomic symptoms in the form of functional hyperthermia were completely reduced or manifested in short-term episodes during periods of exacerbation.

Psychovegetative symptom complex with functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract

29 patients (12 children under 7 years old and 17 adolescents 12-17 years old) with functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (various types of dyskinesia, reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.) were examined.

Pre-manifest mental disorders (when manifested in the form of gastroenterological symptoms) occurred in this group both episodically and permanently within the framework of the personality-neurotic, affective or neurotic register. As in the previous group, pathological sensations simulating physical diseases predominated. The most typical were intestinal colic, manifestations of irritable bowel syndrome with disturbances in stool frequency, various painful sensations in the abdomen (bloating, seething, etc.). In manifest states and subsequently, such sensations were the most typical, becoming a manifestation of senestopathic symptoms. Various fears of varying depth were also revealed - from situational to delusional.

In the younger age group, psychopathological disorders in the manifest attack were in the nature of senestopathic depressive states with a varied, predominantly anxious, type of affect. Disorders of the neurotic range (obsessive, asthenoadynamic) also arose.

In the older age group, senestopathic depression also dominated, but depressive symptoms of various types (melancholy-vital, anxious, etc.) were more pronounced, including states of asthenic incompetence, hypochondriacal depression, as well as depression with anorexic-bulimic disorders, suicidal tendencies, ideas relationship. The localization of senestopathies changed with the spread to other areas (cephalgia, cardialgia, etc.).

Psychovegetative symptom complex with polymorphic vegetosomatic disorders

In the group of patients with polymorphic vegetosomatic disorders (vegetative-vascular dystonia - VSD; functional skin disorders, respiratory pseudoasthmatic attacks, etc.) 25 patients were observed: 10 preschool children under 7 years old and 15 adolescents 12-17 years old.

The absence of pre-manifest psychopathological disorders and personal and behavioral deviations was revealed in only 2 patients. At the same time, the greatest polymorphism of pre-manifest psychopathological disorders was noted without a noticeable predominance of any symptoms. The manifestation of autonomic disorders occurred against the background of an intensification of previous psychopathological symptoms in the form of an acute psychovegetative attack, reminiscent of panic attacks (raptoid anxiety states) in adults, often accompanied by thanatophobia. Compared with other groups, the patients had more pronounced various manifestations of depersonalization disorders, primarily somatopsychic depersonalization.

In adolescence, age-related dynamic features were determined that were fundamentally similar to other groups, including a clear dependence of vegetative and psychopathological symptoms with a predominance of the latter in clinical manifestations. In general, no such dependence was found in only 1/10 patients. This dependence was most indicative of the parallel (psychotropic and vegetotropic) effect of psychopharmacotherapy - both positive (in the case of effective treatment) and negative (if it was discontinued).

Thus, in general, analysis of data from a cohort follow-up survey confirms the patterns identified in different age groups of patients. As patients grow up and as vegetative manifestations of psychovegetative diathesis are reduced, psychopathological disorders themselves come to the fore, which subsequently acquire a more monomorphic and, in most cases, reduced character (erased affective disorders, neurotic and neurosis-like manifestations, behavioral disorders, moderate specific endogenous deficiency symptoms , cerebrasthenic signs). Only in isolated cases of heart rhythm disorders was the opposite relationship observed: the persistence of arrhythmia attacks with a significant reduction in psychopathological manifestations. Also, in isolated cases, after long-term stable remission with reduction of both somatovegetative and psychopathological disorders, exacerbations of psychopathological symptoms of the affective and schizoaffective circle occurred at the outpatient level.

Muscular dystonia syndrome in children of the first year of life

Along with perinatal encephalopathy (PEP) and hypertensive-hydrocephalic syndrome, muscular dystonia syndrome is one of the most common diagnoses made by neurologists, as well as pediatricians in our country.

Muscle tone and reasons for its increase

So, muscle tone refers to the resistance of a muscle that occurs when it is passively stretched during movement in a joint . A number of structures of the spinal cord and brain take part in the regulation of muscle tone. For the formation of pathological muscle tone, especially increased (“hypertonicity”), a compelling reason is necessary, leading to damage, disruption of the structure of the brain and/or spinal cord. For example, such causes may be severe hypoxia during childbirth (Apgar score <5 points), trauma, encephalitis, malformation of the brain and/or spinal cord, as well as a number of fairly rare genetic diseases. Thus, in the absence of the compelling reasons described above, the child’s muscle tone deviations from the norm are unlikely.

Let’s look at several of the most common clinical situations where the conclusion “Muscular dystonia syndrome” sounds scary, but is just another case of overdiagnosis.

- In children from birth to 3-3.5 months, the tone of the muscles that flex the limbs is normally increased. This is manifested by a peculiar posture when the child’s legs and arms are predominantly in a bent position. Such manifestations are normal and do not require additional treatment or massage;

- The child's support of the toes and/or stretching of the toes during verticalization at the age of 5-7 months as an isolated symptom occurs within the normal range, is associated with the stages of development of motor function, and is not a sign of pathology, especially as serious as cerebral palsy (CP);

- The term “dystonia” means a violation of the mechanism of regulation of muscle tone of different groups among themselves. When these interactions are disrupted, this is what is called dystonia. The fact is that in the first year of life, especially in the 1st months, children are normally very dystonic, since the formation of interaction and regulation of muscle tone of various groups occurs most actively up to 2 years, especially in the first 14 months. We can see a certain side: movements of the limbs of one half of the body may be more active, the tone is slightly higher. This is often typical for children under 6 months. As the brain and nerve pathways develop, as well as motor skills, symmetry is formed. Massage courses with exercise therapy elements influence this process only indirectly as an exercise, skill training.

In this article we have reflected the most common clinical situations. Of course, everything is not so simple. Therefore, if you suspect a child’s developmental disorders, you should consult a qualified specialist.

Nosko A.S., Ph.D., neurologist.

Top