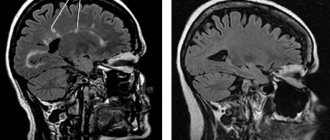

Magnetic resonance imaging, as an advanced diagnostic method, is often used to determine whether a patient has multiple sclerosis. It allows you not only to establish the current condition of a person, but also to track the dynamics of treatment using certain drugs, as well as adjust the course chosen by the doctor.

In this material we will tell you about whether multiple sclerosis is visible on MRI, and we will touch on the features and signs of the disease. We are also ready to answer other questions regarding the examination process.

Features of multiple sclerosis

This is a fairly common disease of the human nervous system, which is characterized by constant progression and development. Patients' motor and speech functions are affected, and there is a high probability of their gradual loss.

Problems with treating multiple sclerosis stem from the fact that the disease is often very difficult to diagnose, especially in the early stages.

The use of magnetic resonance imaging is one of the few methods that can detect the disease and also track its progression.

How does multiple sclerosis occur?

Scientists agree that the disease is provoked by the herpes virus, which can enter the body even in childhood, after diseases such as measles. Since the virus is very similar to myelin, there is a high probability of destruction of such a protein.

The consequence is a decrease in the conductivity of nerve fiber impulses. Against this background, the risk of developing nervous pathology becomes many times greater.

The immune system also suffers. When it is in a normal state, the body defends itself against viruses with all its might. Here again the similarity with myelin comes to the fore. It is this protein that can attack the body's protective barrier, and not the herpes virus. This situation often leads to the formation of multiple sclerosis in humans.

Since the disease is classified as progressive, various external factors can lead to an acceleration of the course or aggravation of the problem.

There are several potential catalysts for the primary process of disease formation or an increase in its activity:

- All types of infectious diseases. Even the common flu can be a catalyst.

- Pregnancy and childbirth. In this regard, it is especially dangerous for women who are already registered with a neurologist to give birth. If you suspect multiple sclerosis, you should avoid pregnancy because it can either start the process or speed it up.

Doctors also recommend that patients with multiple sclerosis spend less time in the sun. Aggressive exposure to ultraviolet radiation can significantly reduce immunity. This provokes the development of various viruses and the body’s immune response.

How is the procedure done?

Brain MPT procedure

painless and does not require special preparation. The average duration is 30 minutes. For examination, the patient lies down on the retractable table of the device in a stationary position. The table then slides inside the cylinder of the scanning machine.

The tomograph takes many pictures in various projections and modes. After the procedure, the specialist will be able to see the result on the computer and begin decoding.

What signs can be used to diagnose multiple sclerosis?

It is important to pay close attention to your condition in order to identify signs of sclerosis at an early stage. Anyone who has ever noticed herpes is at risk.

Some of the most noticeable signs of multiple sclerosis on MRI include:

- Short-term decrease in vision. Often a person does not pay attention to this, attributing everything to problems with blood pressure. In this case, the vision initially becomes dark, and then vision either disappears or becomes severely deteriorated for several hours.

- Weakness in the limbs. Patients complain that their legs or arms begin to go numb and lose strength. This can happen to one or more limbs.

- Problems with urination. Usually associated with a sudden, acute and very strong urge to urinate. Many people think that if they do not go to the toilet immediately, involuntary emptying of the bladder may occur.

- Damage to the facial nerve. It occurs if the disease is localized in the area of the brain that is responsible for motor functions. This is how a person can develop pronounced facial asymmetry.

- Facial tic. Another sign of damage to the facial nerve. Usually worsens during the cold season. Many doctors miss this sign, thinking that it is associated with a simple cold of the facial nerve. But a few years later it turns out that it was multiple sclerosis that manifested itself this way.

- Impaired coordination of movements. Often a person is unable to maintain a normal position when walking. He begins to stagger as if drunk. At the same time, there is no feeling of dizziness or any other associated reasons that could make walking difficult. It usually occurs in attacks and can pass quickly.

A doctor can also issue a referral for an MRI based on the results of special types of research, for example, vibration exposure.

Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: Revision of the 2010 McDonald criteria

New evidence and consensus have led to further revision of the McDonald criteria for diagnosing multiple sclerosis. The use of imaging to demonstrate dissemination of CNS lesions in space and time is simplified and in some circumstances can be determined by a single scan. This revision simplifies the Criteria, maintains their diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, while addressing their applicability to different populations, and allows for earlier diagnosis and more uniform and widespread use.

Translation ANN NEUROL 2011;69:292–302

For the basics of imaging, read the publication Multiple Sclerosis

Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) include clinical and paraclinical laboratory findings 1,2 to demonstrate dissemination in space (DIS) and time (DIT) and to exclude other diseases. Although diagnosis can be made based on clinical findings alone, MRI of the central nervous system (CNS) can support, complement, and even replace some clinical criteria, 3–9 as most recently highlighted by the so-called McDonald criteria by the international panel for the diagnosis of MS. The McDonald criteria have resulted in earlier diagnosis (MS) with a high degree of specificity and sensitivity, allowing for better patient counseling and earlier treatment. Since the 2005 revision of the criteria, new evidence and consensus indicate a need to simplify them to improve their understanding and usefulness and to suit populations other than Western Caucasian adults for which the criteria were developed. In May 2010, in Dublin, Ireland, the International Panel on the Diagnosis of MS (the panel) met for the third time to examine the requirements for demonstrating DIS and DIT and for the use of the McDonald criteria in pediatric, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Considerations for revising the McDonald criteria

The panel reviewed published research regarding the diagnosis of MS using the original and revised McDonald criteria, collected from English-language literature publications containing the terms multiple sclerosis and diagnosis. The panel concluded that recent research supports the usefulness of the McDonald criteria for adult Western Caucasian populations seen in MS centers, discussing only limited experience in general neurological practice. In these discussions, the panel emphasized that the McDonald criteria should only be applied to patients with typical clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) suggestive of multiple sclerosis or symptoms consistent with inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system because the development and significance of the criteria is limited to such patients. Manifestations of CIS may be monofocal or multifocal, typically involving the optic nerve, brainstem/cerebellum, spinal cord, or cerebral hemispheres. When applying the McDonald criteria, it remains necessary to rule out alternative diagnoses. The differential diagnosis of MS has been the subject of previous guidelines, which identify common and less common alternative diagnoses and identify clinical and paraclinical “red flags” that should indicate specific diagnostic risks. In this review, the panel focuses on the often problematic differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica (NMO) and related disorders. There is an increase in recurrent demyelinating CNS disease involving the optic nerve (unilateral or bilateral), often with significant myelopathy with extensive spinal cord involvement on MRI, often with a normal brain on MRI (or changes atypical for MS), and serum aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibodies. There was agreement that this phenotype should be distinguished from typical MS due to its different clinical course, prognosis, pathophysiology, and poor response to therapy. The panel recommends that these disorders be carefully considered in the differential diagnosis in all patients with clinical and MRI features suggestive of NMO, especially if:

- myelopathy, on MRI with damage to more than 3 segments and with primary involvement of the central part of the spinal cord on axial sections.

- Optic neuritis is bilateral, severe and accompanied by edema, damage to the chiasm and vertical (altitudinal) scotoma.

- Persistent hiccough or nausea/vomiting for more than 2 days with MRI-detected changes around the water supply.

In patients with such features, the AQP4 serum test should be used to facilitate the differential diagnosis between NMO and MS to avoid misdiagnosis and treatment. Correct interpretation of symptoms and signs is a fundamental precondition for diagnosis. The panel again decided that an attack (relapse, exacerbation) is a patient-reported symptom or objectively observed sign typical of an acute demyelinating inflammatory process of the central nervous system, present or past, lasting at least 24 hours, in the absence of fever or infection. Although a new attack should be confirmed by contemporary neurological examination, in some cases, a history of symptoms and a course consistent with MS that are not confirmed can provide confirmation of a previous demyelinating event. Reports of paroxysmal symptoms (history or current) must, however, consist of multiple episodes occurring over at least 24 hours. The panel agreed that before a diagnosis of MS can be made, at least 1 attack must be confirmed by neurological examination, visually evoked potentials (VEPs) in patients with a history of visual impairment or changes on MRI in areas consistent with anamnestic neurological symptoms. The panel decided that the core concepts of the original (2001) and revised (2005) McDonald criteria are still valid, including the ability to establish a diagnosis of MS based on objective demonstration of dissemination in both space and time, based on clinical data alone, or careful and standardized integration of clinical findings. data and MRI data. However, the panel is now recommending key changes to the McDonald criteria related to the use and interpretation of imaging criteria for DIS and DIT, as articulated in recently published work from the MAGNIMS Research Group. These changes are intended to increase diagnostic sensitivity without sacrificing specificity, simplifying the requirements for demonstrating both DIS and DIT while reducing the need for MRI studies. The panel also makes specific recommendations for the application of the McDonald criteria in pediatric, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Recommended Modifications to the McDonald Criteria: 2010 Revision

MRI CRITERIA FOR DIS. In past versions of the McDonald criteria, MRI detection of DIS was based on the Barkhof/Tintore criteria. Despite good sensitivity and specificity, these criteria were difficult to use by non-radiology specialists.

TABLE 1: 2010 McDonald Criteria for DIS DIS can be demonstrated by ≥ 1 T2 lesiona in at least 2 of 4 CNS regions: Periventricular Juxtacortical Infratentorial Spinal Cordb Based on Swanton et al. 2006, 2007. aGadolinium enhancement is not required for DIS. bFor spinal or brainstem syndrome, symptomatic lesions are excluded from the criteria and are not taken into account. MRI = MRI; DIS = spatial dissemination; CNS = central nervous system

The European multicenter MAGNIMS research network studying MRI in MS compares the Barkhof/Tintore criteria for DIS with simplified criteria developed by Swanton et al. In MAGNIMS work, dissemination in space (DIS) can be demonstrated by 1 T2 lesion in 2 of the 4 MS sites defined in the original McDonald criteria (juxtacortical, periventricular, infratentorial, and spinal cord), with lesions within symptomatic region, excluding patients with brainstem or spinal cord syndromes. In 282 CIS patients, the Swanton DIS criteria were shown to be simpler and slightly more sensitive than the original McDonald criteria for DIS, without compromising specificity and accuracy. The College has adopted these MAGNIMS DIS criteria, which can simplify the MS diagnostic process while maintaining specificity and improving sensitivity (Table 1).

MRI CRITERIA FOR DIT. The 2005 revision of the McDonald criteria simplified MRI evidence of dissemination in time (DIT), basing it on the appearance of a new T2 lesion on versus MRI performed at least 30 days after the onset of clinical manifestations. In clinical practice, however, there are reasons not to delay the MRI for 30 days, which leads to an additional repeat MRI examination to confirm the diagnosis.

TABLE 2: MacDonald 2010 Criteria for DIT DIT can be demonstrated:1. New T2 and/or gadolinium-enhancing lesion(s) on follow-up MRI, regardless of the time of the first MRI examination2. Simultaneous presence of asymptomatic enhancing and non-enhancing lesions at any time Based on Montalban et al. 2010.24 MRI = MRI; DIT = dissemination over time.

Exclusion of additional MRI after 30 days does not reduce specificity and therefore the panel in its current revised edition of the McDonald criteria allows confirmation of DIT when a new T2 lesion appears, regardless of the time of the first MRI scan. The MAGNIMS group later confirmed previous studies showing that in patients with typical CIS, a single MRI demonstrating DIS as well as asymptomatic enhancing and nonenhancing lesions was highly specific for predicting early onset clinically definite MS (CDMS) and reliably replaced prior MRI criteria for DIT. After reviewing these data, the panel accepted that the presence of both gadolinium-enhancing and non-enhancing lesions on the initial MRI examination can replace follow-up MRIs to confirm DIT (Table 2), just as it is reliably determined that gadolinium-enhancing lesions are not due to pathology other than MS. Using the recommended simplified MAGNIMS criteria for confirming DIS and allowing confirmation of DIT in the presence of gadolinium-enhancing and non-enhancing lesions in areas typical of MS, the diagnosis of MS can be made in some CIS patients based on a single MRI. The Board considers this justified because it simplifies the diagnostic process without reducing accuracy. However, a new clinical episode or follow-up MRI to identify new enhancing or T2 lesions may still be required to confirm DIT in patients who have both non-gadolinium-enhancing and non-enhancing lesions simultaneously on the initial MRI examination.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CSF ANALYSIS IN DIAGNOSTICS. The panel confirmed that positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests (elevated immunoglobulin G [IgG] index or 2 or more oligoclonal bands) may be important in confirming the inflammatory demyelinating nature of the condition, in evaluating alternative diagnoses, and in predicting CDMS (clinically defined MS). . In the 2001 and 2005 McDonald criteria, positive CSF findings were used to reduce the requirement for MRI to confirm DIS criteria (2 or more MRI-identified lesions consistent with MS if CSF tests were positive). However, the panel believes that when applying the simplified MAGNIMS criteria for DIS and DIT, further liberalization of the MRI requirements in patients with positive CSF tests is not appropriate, since the status of the CSF was not assessed in any way for its contribution to the MAGNIMS criteria for DIS and DIT. To confirm their additional diagnostic value, further studies are needed based on standardized methods and the most sensitive methods for detecting oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, together with new requirements for MRI.

DIAGNOSIS OF PRIMARY PROGRESSIVE MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. In 2005, the panel recommended the revised McDonald criteria for diagnosing primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). In addition to 1 year of disease progression, 2 of the following 3 signs: positive MRI of the brain (9 T2 lesions or 4 or more T2 lesions with positive (VEP) visual evoked potentials); positive MRI findings of the spinal cord (2 focal T2 lesions); or a positive CSF test. These criteria reflected the specific role of both CSF testing and spinal cord MRI in primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS), having been found to be practical and well accepted by the neurological community and used as inclusion criteria for clinical trials of PPMS. To harmonize MRI criteria within the diagnostic criteria for all forms of MS, recognizing the special diagnostic needs for PPMS, the panel recommends that the McDonald criteria requirement include 2 of the 3 MRI criteria or CSF analysis for PPMS, replacing the previous MRI brain criteria, new MAGNIMS criteria for DIS (2 of the following 3:

- One T2 lesion in at least one area characteristic of MS /periventricular, juxtacortical or infratentorial/;

- Two T2 lesions in the spinal cord or a positive cerebrospinal fluid analysis (isoelectric focusing the presence of oligoclonal bands and/or an increased IgG index) (Table 3).

TABLE 3: 2010 McDonald Criteria for the Diagnosis of Primary Progressive MS PPMS can be diagnosed using:

- One year of disease progression (retrospectively or prospectively determined)

- Plus 2 of the following 3 criteriaa: DIS in the brain based on ≥ 1 T2b lesions in at least 1 typical MS region of the central nervous system (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial)

- DIS in the spinal cord is based on ≥ 2 T2b lesions in the spinal cord

- Positive CSF tests (oligoclonal bands and/or elevated IgG index

a If the patient has a brainstem or spinal syndrome, all symptomatic lesions are excluded from the Criteria.

b No contrast-enhancing lesions are required.

MS = multiple sclerosis; PPMS = primary progressive multiple sclerosis; DIS = spatial dissemination; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; IgG = immunoglobulin G.

This consensus recommendation is supported by comparisons of diagnostic criteria for PPMS and subsequent reanalyses of these data (X. Montalban, personal communication). The use of MRI criteria for PPMS based on MAGNIMS, with or without CSF assessment, should be supported by additional data, further confirming the sensitivity and specificity of the criteria in this population.

APPLICATION OF THE MACDONALD CRITERIA IN PEDIATRIC, ASIAN, AND LATIN AMERICAN POPULATIONS. The McDonald criteria were developed based on data collected primarily from adult European and North American populations, and their applicability to other populations is questionable, including pediatric cases, Asians, and Hispanics.

Pediatric MS

Over 95% of pediatric patients with MS have a relapsing-remitting disease course, since PPMS is exceptional in children and should suggest an alternative diagnosis. About 80% of pediatric cases, and almost all juvenile cases, present with attacks typical of adult clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), with similar or larger overall T2 involvement. In children under 11 years of age, the lesions are larger and less clearly demarcated than in adolescents. MRI criteria for DIS have high sensitivity and specificity. The panel concluded that the MAGNIMS MRI criteria for DIS are well suited for most pediatric patients with multiple sclerosis, especially those with acute demyelination presenting as CIS, because most have more than 2 lesions and are very likely to have 2 of 4 lesions. x specific localizations (periventricular, trunk-infratentorial, juxtacortical, spinal cord). The incidence of spinal cord injury in pediatric MS is not currently reported, but the presence of spinal cord injury with spinal symptoms is generally similar to that in adults. However, approximately 15-20% of pediatric patients with MS, most younger than 11 years of age, present with encephalopathy and multifocal neurological deficits difficult to distinguish from acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Current international consensus criteria for diagnosing MS in children with an ADEM-like first attack require evidence of 2 or more non-ADEM-like attacks, or 1 non-ADEM-like attack followed by accumulation of clinically silent lesions. Although children with ADEM-like first attack MS are more likely than children with monophasic ADEM to have 1 or more nonenhancing T1 hypointense lesions, 2 or more periventricular lesions, and no pattern of diffuse lesions, these findings are not entirely distinctive. In addition, MRI in children with monophasic ADEM typically demonstrates multiple variable enhancing lesions (often >2) typically located in the juxtacortical white matter, infratentorial, and spinal cord. Thus, application of the revised MAGNIMS criteria for DIS and DIT on initial MRI would be inappropriate for these patients, and serial clinical and MRI studies are required to confirm the diagnosis of MS. In this age group, resolution of lesions may occur before new lesions and attacks occur over time, leading to a diagnosis of MS.

MS in Asian and Hispanic populations

Among Asian patients with inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system, a phenotype characterized by NMO (neuromyelitis optica), longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions, and AQP4 antibody seropositivity were comparatively more common than in Western populations. The College sought input on the use of the McDonald Criteria in Asia and Latin America, where there is evidence of such phenotypic differences. Although the McDonald criteria are widely used in these parts of the world, there is some uncertainty, especially in Asia, whether MS and NMO are distinguishable, and if so, how to distinguish them. The term opticospinal MS is now thought to be a combination of regular MS and NMO. Confusion arose:

- due to the fact that most cases of NMO are recurrent;

- whereas AQP4 autoantibody testing has facilitated the diagnosis of NMO and allowed the inclusion of individuals with symptomatic brain lesions who were previously excluded;

- because isolated involvement of the optic nerve and the spinal cord alone does not differentiate NMO from MS.

A diagnosis of NMO cannot be made in the absence of the required revised Wingerchuk specific criteria for “definite” NMO, which recommend the presence of optic neuritis, acute myelitis and at least 2 of 3 additional paraclinical signs (extended spinal involvement of at least 3 segments, MRI of the brain performed at the onset of the disease is negative for MS, or NMO-IgG seropositive). These criteria are successful in most cases in differentiating NMO from MS in patients with optic neuritis and myelitis, but the spectrum of NMO includes recurrent myelitis and optic neuritis, and NMO syndrome with symptomatic lesions in the brain and NMO associated with systemic autoimmune diseases. Misdiagnosis of NMO can complicate treatment. The panel recommends AQP4 autoantibody testing with validated assessments for patients with suspected NMO or NMO-like disorders, especially for patients of Asian and Hispanic origin due to the higher prevalence of the disease in this population. Such testing may be less important for subjects with common Western type MS. Although not all patients with NMO-like manifestations are AQP4 antibody positive, most are, as patients with MS are more likely to be AQP4 antibody negative. It is hereby proposed that once NMO and NMO-like disorders have been excluded, Western-type MS in Asian or Hispanic populations is not fundamentally different from typical MS in Caucasian populations and that the MAGNIMS MRI criteria should be applied to these patients, although confirmatory studies should be done.

MacDonald Criteria: Revision 2010

APPLICATION OF CRITERIA. The panel recommends revised criteria for the diagnosis of MS (Table 4), particularly focusing on the requirement to demonstrate DIS and DIT, and on the diagnosis of PPMS. The 2010 revised McDonald criteria are likely to be applicable in pediatric, Asian, and Hispanic populations once other potential explanations for clinical presentation have been thoroughly evaluated. The predictive validity of the DIS and DIT based on a single first scan in children with CIS needs to be confirmed in subsequent studies. The McDonald criteria have not yet been validated in Asian and Hispanic populations, and studies are needed to confirm the sensitivity and specificity of the criteria in these patients. Care must be taken to exclude NMO, the differential diagnosis of which may be difficult due to the incomplete sensitivity of AQP-4 antibody studies, the presence of brain lesions in NMO, and the difficulty of detecting extensive spinal cord lesions in immunocompromised patients.

TABLE 4: McDonald's 2010 criteria for the diagnosis of MS Clinical manifestations Additional data required for the diagnosis of MS ≥ 2 attacksa; objective clinical presence of ≥ 2 lesions or presence of 1 lesion with a documented history of attackbNo c≥ 2 attacksa; objective clinical presence of 1 lesion Spatial dissemination confirmed by ≥ T2 lesions in at least 2 of 4 typical MS regions of the central nervous system (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial or spinal cord)d; or expect a new clinical attacka affecting a different area of the central nervous system1 attacka; objective clinical presence of ≥ 2 lesions Dissemination over time, confirmed by: the simultaneous presence of asymptomatic enhanced and non-enhanced lesions at any time; or new T2 and/or enhancing lesion(s) on follow-up MRIs, regardless of time compared to the initial MRI; or expect a new clinical attacka1 attacka; objective clinical presence of 1 lesion (clinically isolated syndrome) Dissemination in space and time, confirmed: For DIS: ≥ 1 T2 lesion in at least 2 of 4 typical MS regions of the central nervous system (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial or spinal cord )d; or expect a new clinical attacka involving a different area of the central nervous system For DIT: the simultaneous presence of asymptomatic enhancing and non-enhancing lesions at any time; or new T2 and/or enhancing lesion(s) on follow-up MRIs, regardless of time compared to the initial MRI; or expect a new clinical attacka Insidious neurological progression resembling MS (PPMS)1 year of disease progression (retrospectively or prospectively determined) plus 2 of the 3 following criteriad:

- Spatial dissemination confirmed by ≥ 1 T2 lesions in at least 2 of 4 typical MS sites (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, or spinal cord).

- Spatial dissemination in the spinal cord based on ≥ 2 T2 lesions

- Positive cerebrospinal fluid tests (isoelectric focusing the presence of oligoclonal bands and/or increased IgG index)

If the criteria completely match, and there is no better explanation for the clinical manifestations, then the diagnosis is “MS”. If there is a suspicion, but the criteria are not fully established, the diagnosis is “probable MS”; if another diagnosis arises that better explains the clinical manifestations, the diagnosis is “not MS”.

a An attack (exacerbation, relapse) is defined as a patient-reported or objectively detected event typical of an acute inflammatory demyelinating process in the central nervous system, present or past, lasting at least 24 hours, in the absence of fever or infection. The attack should be documented by contemporary neurological examination, but certain symptomatic history events and developments characteristic of MS without documented objective neurological findings may provide reasonable confirmation of a previous demyelinating event. Indications of paroxysmal symptoms (history or present) must, however, consist of multiple episodes lasting at least 24 hours. Before a definitive diagnosis of MS is made, at least 1 attack must be confirmed by neurological examination, visual evoked potentials in patients with a history of visual impairment, or MRI data with foci of demyelination in areas of the central nervous system consistent with the location of the history of neurological symptoms.

b Clinical diagnosis based on objective clinical data from 2 attacks is the most reliable. Reasonable anamnestic evidence of 1 previous attack in the absence of documented objective neurological findings may include a history of an event with symptoms and course consistent with an inflammatory demyelinating event. But at least 1 attack must be confirmed by objective data.

c No additional research required. However, it is advisable that any diagnosis of MS be made using imaging based on these criteria. If performed MRI or other tests (eg, CSF) are negative, the diagnosis of MS should be made with great caution, considering other alternative diagnoses. There must be no better explanation for the clinical manifestations and there must be objective confirmation of the diagnosis of MS.

d Contrast-enhancing lesions are not required, and symptomatic lesions are not counted in patients with brainstem or spinal syndrome.

MS = multiple sclerosis; CNS = central nervous system; MRI = MRI; DIS = spatial dissemination; DIT = dissemination over time; PPMS = primary progressive multiple sclerosis; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; IgG = immunoglobulin G.

Future directions

POTENTIAL ADDITIONAL VALUE OF BIOMARKERS. Although an elevated IgG index or the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid support the diagnosis of MS, and testing for AQP4 antibodies can help in differential diagnosis, there are still no specific biomarkers to confirm the diagnosis. Several blood and CSF biomarkers may show promise, and high-resolution spectral optical coherence tomography might be as good as VEP in assessing visual involvement. The diagnostic utility of such markers remains to be confirmed and tested in the future.

CLARIFICATION OF VISUALIZATION CRITERIA. The MacDonald criteria are based on the identification of lesions, usually using 1.5T MRI, outside the cerebral cortex and in the spinal cord. However, the majority of MS lesions are located in the cortex and can be detected using a double inversion-recovery sequence. The presence of at least 1 lesion in patients with CIS may help place them at high risk for developing CDMS. Magnetic fields greater than 1.5T with appropriate protocols can also improve diagnostics, with improvements in image resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and chemical shift. 7.0T scan demonstrates lesions in white and gray matter with in vivo enhancement, revealing pathological signs of MS lesions. Finally, MRI techniques such as magnetization transfer can detect lesions outside of focal lesions (eg, in normal-appearing brain tissue) not present in conditions such as ADEM and NMO. The usefulness of these scanning technologies for diagnosing MS in patients with CIS remains a subject for future research and requires confirmation. Many patients with a large number of lesions may have had a long subclinical course of the disease before their first clinical manifestation. Also, in random patients examined on MRI for indications unrelated to MS, changes may be detected that are similar in appearance and location to MS lesions. This presymptomatic phase or radiologically isolated syndrome is detected very often. Some were followed clinically and subsequent MRI studies demonstrated DIT on MRI and some developed clinical manifestations several years later. However, in the absence of supporting research data, the panel concluded that a firm diagnosis of MS based only on MRI findings without important clinical symptoms is problematic even with the additional evidence of evoked potentials and characteristic changes in the cerebrospinal fluid. In the future, a definite diagnosis of MS, however, cannot be excluded and may be probable, depending on the evolution of neurological symptoms.

Conclusion

The 2010 revision of the McDonald criteria allows for faster diagnosis of MS in some cases, with equivalent or improved specificity and/or sensitivity compared to past criteria, and will in many cases simplify the diagnostic process with fewer MRI studies required. A proportion of patients with nonspecific symptoms (fatigue, weakness, dizziness) and nonspecific MRI findings presented to secondary and tertiary MS centers in developed countries for a second opinion and actually did not have MS. Therefore, the revised McDonald criteria for diagnosing MS should only be used for patients with typical CIS (or progressive paraparetic/cerebellar/cognitive syndrome if PPMS is suspected). The Panel recognizes that the use of these improved diagnostic criteria may alter the results of some patients in natural history studies and clinical trials where original outcome expectations may be based on subjects whose diagnosis was made based on historical, somewhat different, criteria. Most of the currently recommended fixes are based on new data generated since the 2005 fixes. However, there remains a need for further testing with prospective and retrospective data collection for many of these criteria, particularly in the patient population typical of general neurological practice, both to advance the assessment of their significance and utility and to provide suggestions for further improvements in future.

How to Detect Multiple Sclerosis Using MRI

In the medical community, magnetic resonance imaging is considered one of the most effective methods for diagnosing this type of disease. The technique allows you to obtain clear and understandable indications about the patient’s condition.

The first step in diagnosis is an MRI of the brain. Much attention is paid to how powerful the tomograph is used in the process. It should create a magnetic field of 1.5 Tesla.

The power requirement is due to the fact that in the early stages of disease progression, its foci are usually local and inconspicuous. To improve visibility, a special contrast agent is administered.

Will an MRI without contrast show multiple sclerosis?

In later stages it will show; in earlier stages there is a possibility that the lesion will go unnoticed.

If magnetic resonance imaging shows that the patient has signs of multiple sclerosis, an additional examination of the spinal cord may be prescribed. MRI is also used for this purpose.

It is important that the treating physician rely on more than just the use of magnetic resonance imaging. It is also necessary to collect a detailed medical history and perform various options for additional neurological tests.

Having clear MRI images in your doctor’s hands helps you quickly make a primary diagnosis and collect a list of recommendations that will help you begin quick and effective treatment.

Signs of multiple sclerosis on MRI of the brain

The presence of multiple sclerosis may be indicated by the following signs detected during MRI of the brain:

- Accumulation of the contrast agent administered before the MP examination in lesions of the brain or spinal cord.

- Dynamics of increase in the size of lesions when repeating the MRI procedure (for example, within a year). Frequent MRI repetitions do not make sense, since multiple sclerosis develops quite slowly.

- The appearance of edema around the focus of demyelination.

- Damage not only to the nerve sheath, but also to the brain stem and cerebellum.

In addition, MPT can help identify problems such as compression of nerve endings by the bones of the spine. This can happen if the patient suffers from osteochondrosis, intervertebral hernia and other diseases of the musculoskeletal system. Such a negative effect on the spinal cord can be one of the root causes of the development of multiple sclerosis.