Even (or precisely for this reason) such a complex device as the human psyche “jumps”—it is subject to cognitive distortions. Some of them are obvious, so it’s easy to fight them; it’s enough to be aware of them. But others are confusing and you can’t figure them out quickly. One of these complex phenomena is causal attribution, a phenomenon of human perception.

Gestalt psychologist Fritz Heider is considered the “father” of causal attribution, which he wrote about back in the 1920s. In his dissertation, Haider addresses the problem of information perception and how a person interprets it. After him, many scientists began to study the phenomenon in more detail. We will talk about their theories later, but first we will deal with the concept itself.

Types of causal attribution

Wikipedia defines the term as follows: causal attribution (from Latin causa - cause, Latin attributio - attribution) - a phenomenon of interpersonal perception. It consists of interpreting, attributing reasons for another person’s actions in conditions of a lack of information about the actual reasons for his actions.

Trying to find the reasons for other people's behavior, people often fall into the traps of prejudice and error. As Fritz Heider said: “Our perception of causality is often distorted by our needs and certain cognitive distortions.”

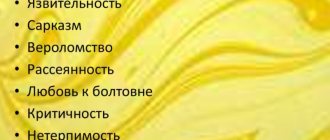

Here are examples of cognitive distortions due to causal attribution.

Fundamental attribution error

The fundamental attribution error is the explanation of other people’s actions by internal factors (“this person is a bore” – internal disposition), and one’s own actions by external circumstances (“events unfolded in such a way that I could not have done anything differently” – external disposition). It becomes most obvious when people explain and assume the behavior of others.

Reasons for fundamental attribution:

- Unequal opportunities: ignoring the characteristics determined by the role position.

- False agreement: viewing one's behavior as typical and behavior that differs from it as abnormal.

- More trust in facts than in judgments.

- Ignoring the informational value of what did not happen: what was not done should also be the basis for evaluating behavior.

Example one: your friend failed the exam that you both took. He always seemed to have a low level of knowledge. You begin to think that he is lazy, doing everything but studying. However, it is possible that he has problems remembering information or some difficult circumstances in the family that interfere with preparing for exams.

Example two: a stranger’s car won’t start. You decide to help him by giving him some practical advice. He disagrees with them or simply ignores them. You become angry and begin to perceive this person as rude and rejecting sincere help. However, he's probably been given the same advice before and it didn't work. After all, he just knows his car better. Or he was having a bad day.

Note that we are talking about internal disposition. If we talk about external ones, then if you do not pass the exam, then, most likely, you will explain this not by the low level of your knowledge, but by bad luck - you got the most difficult ticket. And if your car doesn’t start, then the person who is trying to help/being smart, even though he wasn’t asked, will be to blame.

External disposition is not necessarily bad. This is to some extent a defense mechanism because you don’t feel guilty, don’t spoil your mood and look at the world optimistically. But it can also lead to a constant search for excuses and personality degradation.

Cultural prejudice

It occurs when someone makes assumptions about a person's behavior based on their cultural practices, background, and beliefs. For example, people from Western countries are considered to be individualists, while Asians are collectivists. Well, you’ve probably heard more than one joke about Jews, Armenian radio and representatives of many other nationalities.

Difference between participant and observer

As already noted, we tend to attribute the behavior of other people to our dispositional factors, classifying our own actions as situational. Therefore, attribution may vary from person to person depending on their role as a participant or observer - if we are the main actor, we tend to view the situation differently than when we are simply observing from the outside.

Dispositional (characteristic) attribution

It is the tendency to attribute people's behavior to their dispositions, that is, to their personality, character, and abilities. For example, when a waiter treats his customer rudely, the customer may assume that he has a bad character. There is an instant reaction: “The waiter is a bad person.”

Thus, the customer succumbed to dispositional attribution, attributing the waiter's behavior directly to his personality, without considering the situational factors that could cause this rudeness.

Self-serving attribution

When a person receives a promotion, he believes that it is due to his abilities, skills and competence. And if he doesn’t get it, then he thinks that the boss doesn’t like him (an external, uncontrollable factor).

Initially, researchers thought that the person wanted to protect their self-esteem in this way. However, later it was believed that when results meet expectations, people tend to attribute this to internal factors.

Defensive attribution hypothesis

The defensive attribution hypothesis is a social psychological term that refers to a set of beliefs that a person holds in order to protect themselves from anxiety. To put it simply: “I am not the cause of my failure.”

Defensive attributions can also be made towards other people. Let's put it in the phrase: "Good things happen to good people, and bad things happen to bad people." We believe this so we don't feel vulnerable in situations where we have no control over them.

In this case, everything goes to the extreme. When a person hears that someone was killed in a car accident, he may assume that the driver was drunk or bought a license, but this will certainly never happen to him personally.

All of the above examples of causal attribution are very similar to cognitive dissonance - a state of mental discomfort in a person caused by a clash in his mind of conflicting ideas: beliefs, ideas, emotional reactions and values. This theory was proposed by Leon Festinger. He formulates two hypotheses for this phenomenon:

- When a person experiences dissonance, he strives with all his might to reduce the degree of discrepancy between two attitudes in order to achieve consonance, that is, correspondence. This way he gets rid of discomfort.

- The person will avoid situations in which this discomfort may increase.

Since you got a D in the exam, why should you feel discomfort because you didn’t prepare at all, right? Not true. To understand this, let's talk about locus of control.

Ways to control external variables

There are four ways to control external variables or, in other words, interference. These are randomization, alignment, statistical control and design control.

Randomization

Randomization is the assignment of test subjects to groups using random numbers. Each of these groups, for example, is shown its own version of a commercial. As a result of this diversity, external factors are distributed more or less evenly. It is important to note that randomization does not help with small samples: external variables are not averaged sufficiently. To ensure the admissibility of randomization, it is necessary to compare the average values of external variables in the groups formed as a result of its implementation.

Matching

This method consists of dividing the set of test objects into classes with similar external characteristics and selecting the same number of similar objects into each group. This method has two disadvantages. Firstly, it is impossible to level out all parameters. Secondly, if the alignment was not carried out according to the parameters required, all the work becomes useless.

Statistical control

We are talking about using the method of variance analysis to assess the significance of the influence of independent variables on dependent ones. In this case, external variables are also taken into account.

Design control

Design control refers to the use of experimental designs specifically designed to eliminate the influence of certain external variables. We will learn about which designs are applicable here in the next subsection.

Causal attribution and locus of control

It should be said that causal attribution is closely related to locus of control.

Locus of control is the characteristic ability of an individual to attribute his successes or failures only to internal or only to external factors.

In the case of causal attribution, there is a double standard. Whereas locus of control shows that a person chooses his own reaction. Having received a bad mark on an exam, he can manifest this locus in two different ways:

- It's my own fault that I got a bad grade. I didn’t prepare much, I walked around, I thought about absolutely the wrong things. I'll fix it and start right now.

- The ticket, the difficult subject, or the teacher are to blame. If it weren't for this, I would get what I deserve.

The difference between causal attribution and locus of control is the presence of willpower in the second case.

To change your locus of control, you must first get rid of the victim syndrome. Take full responsibility even if external factors really greatly influenced the result.

The essence and features of the study

Longitudinal observation can be carried out for research and clinical purposes.

In the first case, we are dealing with a psychological experiment when the reaction of a referent or reference group to certain external changes is studied.

In the second case, longitudinal observation is a method for diagnosing somatic and mental abnormalities in the child’s psyche. The technique is widely used in pedagogy to, for example, identify the consequences of changes in the education system.

An object can be studied both in natural and artificially created environments.

Over a selected period of time, usually long , the object is observed.

The researcher records behavioral changes, interprets the data and formulates a conclusion about the correctness or incorrectness of the desired hypothesis. Repeated recording of readings gives a rich picture of an individual’s development over time.

Longitudinal research is sometimes contrasted with the method of comparison and analogy. However, this is not entirely correct. The comparative method compares two different objects in a certain situation.

In longitudinal observation, two different states of one object are compared, before the influence of an external factor and after this influence.

Thus, if the cross-sectional method compares objects in space, then the “longitudinal method”, the second name for longitudinal observation, compares the states of an object in time.

At the same time, the study can be either prospective or retrospective . In the first case, data collection is carried out during the study, in a specified period of time, in the second case, the researcher interprets data collected in the past.

Typically, the results of the study are depicted in the form of simple graphs with abscissa and ordinate axes.

Development patterns can be linear, nonlinear, or discontinuous.

The main goal of longitudinal observation is to investigate the influence of an external factor on the psychological processes of the referent, test causal (presumptive) hypotheses on specific material, identify deviations and formulate ways to solve it.

Causal attribution and learned helplessness

Causal attribution, interestingly enough, is often used to understand the phenomenon of learned helplessness.

Learned/acquired helplessness is a state of a person in which he does not make attempts to improve his condition (does not try to receive positive stimuli or avoid negative ones), although he has such an opportunity. This happens when he has tried several times to change the situation but failed. And now I’m used to my helplessness.

The father of positive psychology, Martin Seligman, demonstrated in his experiments that people put less effort into solving a “solvable” problem after they had suffered a series of failures at “unsolvable” problems.

Seligman believes that people, having received unsatisfactory results, begin to think that further attempts will also not lead to anything good. But the theory of causal attribution says that people do not try to redouble their efforts in order not to lower their self-esteem, because otherwise they will attribute failure to their internal personal characteristics. If you don’t try, it’s much easier to blame external factors for everything.

Causal attribution theories

The most popular are two of them.

Jones and Davis Correspondence Theory

Scientists Jones and Davis presented a theory in 1965 that suggested that people pay special attention to intentional behavior (as opposed to random or mindless behavior).

This theory helps to understand the process of internal attribution. Scientists believed that a person is prone to making this error when he perceives inconsistencies between motive and behavior. For example, he believes that if someone behaves friendly, then he is friendly.

Dispositional (i.e. internal) attributes provide us with information from which we can make predictions about a person's future behavior. Davis used the term "correspondent inference" to refer to the case when an observer thinks that a person's behavior is consistent with his personality.

So what leads us to draw a correspondent conclusion? Jones and Davis say that we use five sources of information:

- Choice : When behavior is freely chosen, it is said to be driven by internal (dispositional) factors.

- Random or intentional behavior : Behavior that is intentional is more likely to be related to the person's personality, while random behavior is more likely to be related to the situation or external causes.

- Social desirability : You observe someone sitting on the floor, even though there are empty chairs. This behavior has low social desirability (nonconformity) and is likely to be consistent with the individual's personality.

- Hedonic relevance : when another person's behavior is directly intended to benefit or harm us.

- Personalism : When another person's behavior seems likely to affect us, we assume that it is "personal" and not simply a by-product of the situation in which we find ourselves.

Kelly covariance model

Kelly's (1967) covariance model is the most famous attribution theory. Kelly developed a logic model for assessing whether a particular action should be attributed to a characteristic (intrinsic) motive or to the environment (extrinsic factor).

The term covariance simply means that a person has information from multiple observations at different times and in different situations and can perceive covariance between the observed effect and its causes.

He argues that in trying to discover the causes of behavior, people act like scientists. In particular, they consider three types of evidence.

- Consensus : the degree to which other people behave similarly in a similar situation. For example, Alexander smokes a cigarette when he goes to lunch with his friend. If his friend also smokes, his behavior has a high consensus. If only Alexander smokes, then he is low.

- Distinctiveness : The degree to which a person behaves similarly in similar situations. If Alexander smokes only when socializing with friends, his behavior is highly distinctive. If in any place and at any time, then it is low.

- Consistency : The extent to which a person behaves in a manner each time a situation occurs. If Alexander smokes only when socializing with friends, consistency is high. If only on special occasions, then it is low.

Let's look at an example to help understand this attribution theory. Our subject is Alexey. His behavior is laughter. Alexey laughs at a comedian’s stand-up performance with his friends.

- If everyone in the room laughs, consensus is high. If only Alexey, then low.

- If Alexey only laughs at the jokes of a particular comedian, the distinctiveness is high. If she is above everyone and everything, then she is low.

- If Alexey only laughs at the jokes of a particular comedian, consistency is high. If he rarely laughs at this comedian's jokes, she is low.

Now if:

- everyone laughs at this comedian’s jokes;

- and will not laugh at the jokes of the next comedian, given that they usually laugh;

then we are dealing with external attribution, that is, we assume that Alexei laughs because the comedian is very funny.

On the other hand, if Alexey is a person who:

- the only one who laughs at this comedian's jokes;

- laughs at the jokes of all comedians;

- always laughs at the jokes of a particular comedian;

then we are dealing with internal attribution, that is, we assume that Alexey is the kind of person who likes to laugh.

So there are people who attribute causation to correlation. That is, they see two situations following each other and therefore assume that one causes the other.

One problem, however, is that we may not have enough information to make such a decision. For example, if we don't know Alexey very well, we won't necessarily know for sure whether his behavior will be consistent over time. So what should you do?

According to Kelly, we go back to past experiences and:

- We repeatedly increase the number of necessary reasons . For example, we see an athlete winning a marathon and we think that he must be a very strong athlete, train hard and be motivated. After all, all this is necessary to win.

- Or we increase the number of sufficient reasons . For example, we see that an athlete has failed a doping test and we assume that he was either trying to deceive everyone or accidentally took a prohibited substance. Or maybe he was completely deceived. One reason would be enough.

If your English level is above average, you can watch the following video, in which a teacher from Khan Academy explains the term “covariation” in simple words.

Are the events sequenced correctly in time?

We need to make sure that events X and Y occurred in the correct sequence, that is, either first X, then Y, or simultaneously. But not first Y and then X.

Note that the interrelated events X and Y can both be the result of something third. For example, a person can make a lot of purchases in a particular store (X) and have a payment or discount card for this store (Y). What is the cause and what is the effect? After all, it is clear that if a person has a store card, he is drawn to go to this store. And vice versa - if this store is convenient for him, then there is a high probability that he will want to use the card.

Another example. It has been noticed that people are increasingly making purchasing decisions directly in the store. Is this due to more advertising in stores? Or, on the contrary, has there been more advertising because store management has noticed changes in people’s behavior?

Consider again the hypothesis that in-store service leads to increased sales. You need to make sure that first the staff was specially trained or new staff was hired, and sales increased in the following months. Or, let’s say, at the same time there is staff training and, regardless of this, sales are increasing. Both of these options do not contradict the hypothesis of the existence of a causal relationship. But this may not be the case: perhaps the store, having noticed an increase in sales, allocated part of the additional revenue to additional staff training.

Table 1

- In a mathematical sense: the occurrence of event X is a necessary condition for the occurrence of event Y.

- In a mathematical sense: the occurrence of event X is a sufficient condition for the occurrence of event Y.

table 2

3. Is the possible influence of other factors excluded?

Let's return to the example of analyzing the influence of education on the purchase of fashionable clothes. Co-variation with education is observed here, as we have seen. What about the influence of other factors? After all, fashionable clothes are more expensive, and educated people usually earn more! If we also divide respondents by income, we see that this correlation is false: there is practically no difference in percentage between each pair of columns (Table 3). The illusion was created due to the fact that among people with high education there are relatively wealthy three hundred out of five hundred, and among people with low education - only two hundred out of five hundred.

Now let's continue the conversation about service and sales. To conclude that good service increases sales, you need to be sure that other factors have not changed simultaneously with the improvement of service: prices, advertising, breadth of product offerings, product quality, competition, etc.

There are usually so many factors that, studying the situation after the fact, one can never say with certainty whether all of them were excluded.

Let us now assume that we are nevertheless convinced of the presence of joint variation, the correct sequence of events and the absence of other possible influences. What else do we need to make a final conclusion about the existence of a causal relationship? In addition to all this evidence, we must have a meaningful internal understanding of why such a connection can and should exist. Controlled marketing experiments are conducted to test the three conditions we have named and to provide grounds for internal belief.

Conclusion

It is very important to avoid causal attribution, especially when it ruins your life and leads to trouble. Stop your flow of thoughts for a moment and understand the reason for the behavior of a particular person - this is usually enough to avoid making sudden conclusions. This will improve your observation skills and teach you to empathize with others.

In addition, you should understand that there is no problem in attributing your failures to external factors, and your success to internal ones (especially if it is deserved). Just don’t make a blind habit out of it, but look at the situation.

We wish you good luck!

Did you like the article? Join our communities on social networks or our Telegram channel and don’t miss the release of new useful materials: TelegramVKontakteFacebook

Concept

What is a longitudinal study?

Longitudinal research is a set of methods for studying an object or group of objects over a certain period of time.

This method is used in sociology, psychology, and linguistics.

In relation to psychology, we are talking about observing a person over a specific period of time, recording changes in his psychological state , and studying the influence of external factors.