What problems does isotherapy solve?

The main goal of isotherapy is to rid the child of problems such as:

- inability to express feelings and emotions, psychological “stiffness”, nervousness, aggressiveness, fears;

- imbalance, jealousy;

- low self-esteem, which, according to statistics, affects more than 70% of all people;

- erratic behavior;

- chronic stress;

- misunderstanding in the family;

- lack of development of creative potential, hidden capabilities and resources Source: Zautorova, E.V. The role of art and art therapy in the prevention and correction of deviant behavior in adolescents / E.V. Zautorova // Bulletin of psychosocial and correctional rehabilitation work. - 2005. No. 1.

Isotherapy methods

Drawing therapy uses all artistic materials - textured paper, wax crayons, paints and brushes, charcoal, clay, salt dough, plasticine, pastels, pencils, spray bottles, cotton swabs and much more. etc. Let's look at some techniques.

“Marania” technique

This technique is effective for preschoolers and primary schoolchildren; it is a spontaneous drawing, abstract drawing. In simple words, this is staining paper using all available means and methods. The results are bright, emotionally rich drawings in gouache or watercolor, made with a brush or by hand. This technique allows you to show emotions, openly show experiences, explore them; there is no concept of “good” or “bad”, “right” or “wrong”. Sometimes it happens that a bright, light, multi-colored drawing is obtained, which the child paints over with dark colors and “destroys,” which is very significant from a psychological point of view.

"Aquatouche"

First, a gouache drawing is applied to the paper; when it dries, the sheet is covered with black ink. After this, the drawing is immersed in water - the gouache is washed off almost completely, and the ink - partially. The result is a toned image on a black background with blurred borders. Step-by-step work with delayed results is useful for children with attention deficit, as well as those who experience negativism.

"Monotype"

First, the child draws on a smooth surface - plastic, glass, film, etc. - and then transfers this drawing by imprinting onto plain paper and then completes the image with other materials. The final image turns out different from the original one. This is spontaneous self-expression that helps relieve stress, increase creativity, and visualize feelings.

"Drawing with a ball"

Useful for those children who are sure that they cannot draw; the technique develops creativity, helps in diagnosing conditions, and is effective in individual work with withdrawn, aggressive, hyperactive children. The design is created by unwinding a ball of thread onto the floor or table.

"Drawing History"

The child draws an illustration for the story or its possible continuation. The technique allows you to correct inappropriate behavior, resolve internal conflicts, diagnose disorders, and relieve tension.

"Drawing in a circle"

Group work aimed at unity, involving all participants in the process, and increasing self-esteem. Children sit in a circle and take turns drawing together according to the psychologist’s instructions, for example, a fantasy creature: the first child – the head, the second – the torso, etc.

"Plasticine composition"

A drawing on a sheet of paper is created with plasticine, which requires perseverance and effort. The technique is suitable for working with hyperactivity, develops imagination and the sensory sphere.

Sources:

- Kiseleva, T.Yu. Pedagogical art therapy. // Directory of the head of a preschool institution - M.: Publishing house "MCFER", information, 2008. No. 1.

- Zautorova, E.V. The role of art and art therapy in the prevention and correction of deviant behavior in adolescents / E.V. Zautorova // Bulletin of psychosocial and correctional rehabilitation work. - 2005. No. 1.

The information in this article is provided for reference purposes and does not replace advice from a qualified professional. Don't self-medicate! At the first signs of illness, you should consult a doctor.

ISOTHERAPY WITH CHILDREN art therapy in working with children

ISOTHERAPY WITH CHILDREN

The number of methods to make it easier for children to express their feelings when using isotherapy is endless. Working with a child is a process that requires caution and delicacy, a process in which what is happening in the soul of the psychologist interacts with what is happening in the soul of the child. Visual creativity is a powerful means of self-expression, facilitating self-identification and providing an avenue for expressing feelings.

The art therapist builds his relationship with the child in such a way that the child shares his feelings that arise during isotherapy, feelings regarding the approach to performing and solving a task, to the work itself, to the process of creation. As a result, the child begins to become more aware of himself.

Drawing

The child’s self-knowledge deepens through discussion of issues related to developing parts of the picture, highlighting them more clearly, achieving greater clarity by describing shapes, colors, images, objects, people.

First stage:

free activity before the actual creative process is a direct experience. At this stage of isotherapy, children like to “get dirty,” as they call it, first using one material, then another, and then mixing them.

Second phase:

the process of creative work - the creation of a phenomenon, a visual representation. Children are silently lost in interaction with their creative expression, regardless of age (even very young children).

Third stage:

distancing, process of looking. At this stage, it is necessary to place the work in a place where it would be easy to look at. Children are invited to place their work of art in a convenient place for them on a vertical surface (wall, window, cabinet wall, door).

Fourth stage:

verbalization of feelings and thoughts that arose as a result of viewing creative work.

The features of the fourth stage of visual activity are as follows:

1. The psychologist asks the child to describe the picture as if he were the picture, using the word “I”. For example: “I am a picture, there are red lines all over my surface, and in the middle there is a blue square.”

2. Specific objects in the picture are selected so that the child identifies them with something: “Be a blue square and describe yourself: what you look like, what your actions are, etc.”

3. If necessary, ask the child questions to make it easier for him to complete the task: “What are you doing?”, “Who is taking advantage of you?”, “Who is closest to you?” These questions help you enter into the drawing with the child and open up different ways to establish relationships and implement the therapeutic process.

At this stage, further concentration of the child’s attention and heightened awareness are achieved by isolating and examining in detail one or more parts of the drawing. The child is encouraged to work as deeply as possible with a specific part of the picture, especially if he has enough energy and inspiration or if there is an unusual lack of them. Questions that often help here are: “Where is she going?”; “What is this circle thinking about?”; "What is she going to do?"; “What will happen to this?” etc. If the child says “I don’t know”, don’t back down, move to another part of the picture, ask another question, give your answer and ask the child if it is right or wrong.

4. The child is asked to conduct a dialogue between two parts of his picture or two touching or opposite points (such as a road and a car, or a line around a square, or the happy and sad sides of the image).

5. The psychologist asks the child to pay attention to the colors. When making suggestions for how to draw a picture while your child sits with his eyes closed, you can ask him to think about the following: “Think about the colors you are going to use. What do you mean by bright colors? What do dark colors mean to you? Will you use bright or pastel colors, light or dark tones?” Questions are structured in such a way that the child is aware, as much as possible, of what exactly he did, even if he does not want to talk about it.

6. The psychologist works on identification, helping the child “attribute to himself” what he says, describing the picture or its parts. You can ask your child: “Have you ever experienced anything like this?”, “Do you ever do this?”, “Does this apply to your life in any way?”, “Do you have anything to say as pink?” bush of what you could say as a human being?” Similar questions can be asked in a wide variety of forms. They must be asked very carefully and gently.

7. Children do not always clearly imagine their lives, their own feelings and experiences. Sometimes they hold back and are very afraid to express their feelings. Sometimes they are not ready for this. Sometimes it suddenly turns out that they are ready to pour out the feelings that arose while drawing, although they do not transfer the content of the paintings to themselves, but they tell it in such a way that it becomes clear what they would like to say. They express what they need, what they want, but in their own way.

8. At this stage, the drawing is put aside and real life situations or stories that “follow” from the drawing are worked out. Sometimes the situation is clarified very quickly with the help of a direct question, for example, “Does this apply to your life?”, and sometimes the child has spontaneous associations associated with some events in his life. Sometimes, if the child suddenly becomes silent or changes his face, you can ask: “What happened?” And the child begins to talk about some events in his current life or about his past. And sometimes he answers: “Nothing.”

9. The psychologist finds out if there are gaps or empty spaces in the pictures and pays special attention to this fact.

10. The psychologist dwells on those things that come to the fore for the child. In this case, it is necessary to show great interest and persistence.

11. Before moving on to more complex and unpleasant sections, it is recommended to work with what is easier and more enjoyable for the child. Because if you start talking with children about easier things, they become more open in conversation about more difficult ones. Some children have a harder time sharing their sadness before expressing positive emotions. However, this is not true in all cases. Sometimes children who harbor anger feel the need to vent it before they discover positive emotions.

12. Observations are made of external manifestations of behavior: the peculiarities of the tone of the child’s voice, the position of his body, facial expression, gestures, breathing, pauses. Silence can mean controlling, thinking, remembering, worrying, fearing, or being aware of something. You can use these signs in subsequent work.

Working method

Provide your child with a variety of materials to choose from: paper of different sizes (wallpaper is an excellent material), paints, pastels, colored pencils, thick and thin brushes.

When working with visual materials, encourage children to use lines, shapes, light strokes, thick strokes, long and short strokes, bright colors, dark and matte colors, long and short, thin and thick shapes to depict objects.

Ask children to work quickly. If you notice a stereotype, come up with exercises that involve actions that are the opposite of what you are already used to.

Children also enjoy technological gadgets. During exercises that require time intervals, you can use stopwatches and hourglasses.

Texts of instructions for exercises

- “Now you will look at this flower for a minute. I will time it with a stopwatch (hourglass) and then ask you, when the time is up, to draw a drawing of the feelings you felt when you looked at it.”

- “Try to express your world in the form of images presented in colors, lines, shapes, symbols. What the world would look like if it were the way you want it.”

- “Draw what you do when you are angry; what makes you angry."

- “Picture a place that makes you happy; how you feel at the moment; how you would like to feel.”

- “Draw yourself: what you look like now, how you would like to look when you get older; when you get old, when you were younger (at a certain age or in general).”

- “Go back to some time or to some scene. Draw a picture of the time when you felt most energetic.”

- “Draw the time that you remember first, the thing that comes to your mind; family scene; your favorite lunch; dream".

- “Draw where you would like to be: an ideal place, a favorite place. Or a place you don't like; the worst thing you can imagine."

- “Draw how you attract attention; how do you achieve what you want; what do you do when you feel sad, anxious, jealous, lonely.”

- “Draw: happy lines, soft lines, sad lines, angry lines, scared lines, etc.”

- “Draw things that are opposite to each other: weak - strong; happy - unhappy, sad - cheerful; to love - not to love; good bad; happiness - unhappiness; trust-suspicion; separately - together."

- “Draw a gift that you would like to receive. What would you like to give? Who could give this to you? Who could you give this to?”

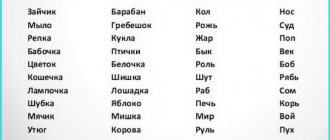

When working with children, you can also pronounce words and invite children to quickly draw what these words mean: love, beauty, anxiety, freedom, mercy, etc.

Many other things can be used as themes for drawings: fantasies, stories, sounds, movements, sights. You can also combine drawing with writing literary works and poetry.

.